A woodblock print created by printmaker Warren Bryan Mack. Title: Delaware River at Shawnee 1939. Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons Jan 24 2026

Across centuries of carving and ink, printmaking has continually transformed—its tools evolving, its surfaces renewed. To many, the shift from carving living wood to carving industrially manufactured linoleum can appear as a modern, disenchanted turn: a movement away from the animate body of the tree toward something processed, abstracted, and seemingly removed. Wood is taken from a standing elder, grown slowly skyward, bearing rings of time and weather. Linoleum, by contrast, is composed of what has fallen and been gathered—materials reduced, recombined, and reformed through human intervention. Because of this, wood and linoleum are often positioned in tension: one ancient and organic, the other modern and manufactured; one alive, the other inert. Yet looking more closely, we can see another story whispering through the fibers. Beneath their apparent differences, wood and linoleum may share a subtle kinship—born of different eras yet shaped by the same material intelligence. This essay attempts to listen more closely to that murmur, asking whether, across time and process, wood and linoleum might be understood not as opposites, but as related kin within a longer material lineage—one that binds tree to fiber, past to present, hand to spirit, and matter to meaning.

The Wood Spirit from European Folklore is often depicted as a "Green Man" or "Woodwose," these carvings are rooted in European, particularly German, traditions where spirits (Waldgeist) were believed to inhabit trees and are custodians of the forest. “Skulpturenweg Theinheim” located in Bavaria, Germany. Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons Jan 24 2026.

Throughout history humanity has carved its marks into many bodies of matter—stone, bone, clay, bronze, gold—each with its own temperament, endurance, and way of meeting the human hand. Across cultures and centuries, artists learned to listen to these materials, shaping their forms in conversation with what each could offer. Among these many relationships, wood became a particularly widespread companion. From Japanese ukiyo-e woodblock prints to Mayan masks, from Nordic stave churches to African sculptural traditions, wood appears again and again, adapting itself to many cultural languages.

This is not because wood is superior, but because it meets certain needs with unusual ease—responding readily to the blade while offering expressive lines, rich textures, and strong contrasts of light and shadow. Its balance of abundance, portability, and workability makes it especially adaptable across contexts. Other materials offer different gifts and ask for different forms of patience. Stone is enduring but slow and labor-intensive, and ill-suited to printing. Metal is powerful and precise, yet costly and dependent on advanced smelting technologies; it would later find its place in movable type. Clay excels at recording and preserving marks, as seen in Mesopotamian tablets, but remains too fragile for repeated printing. Bone and ivory are rare and precious, often limited in scale.

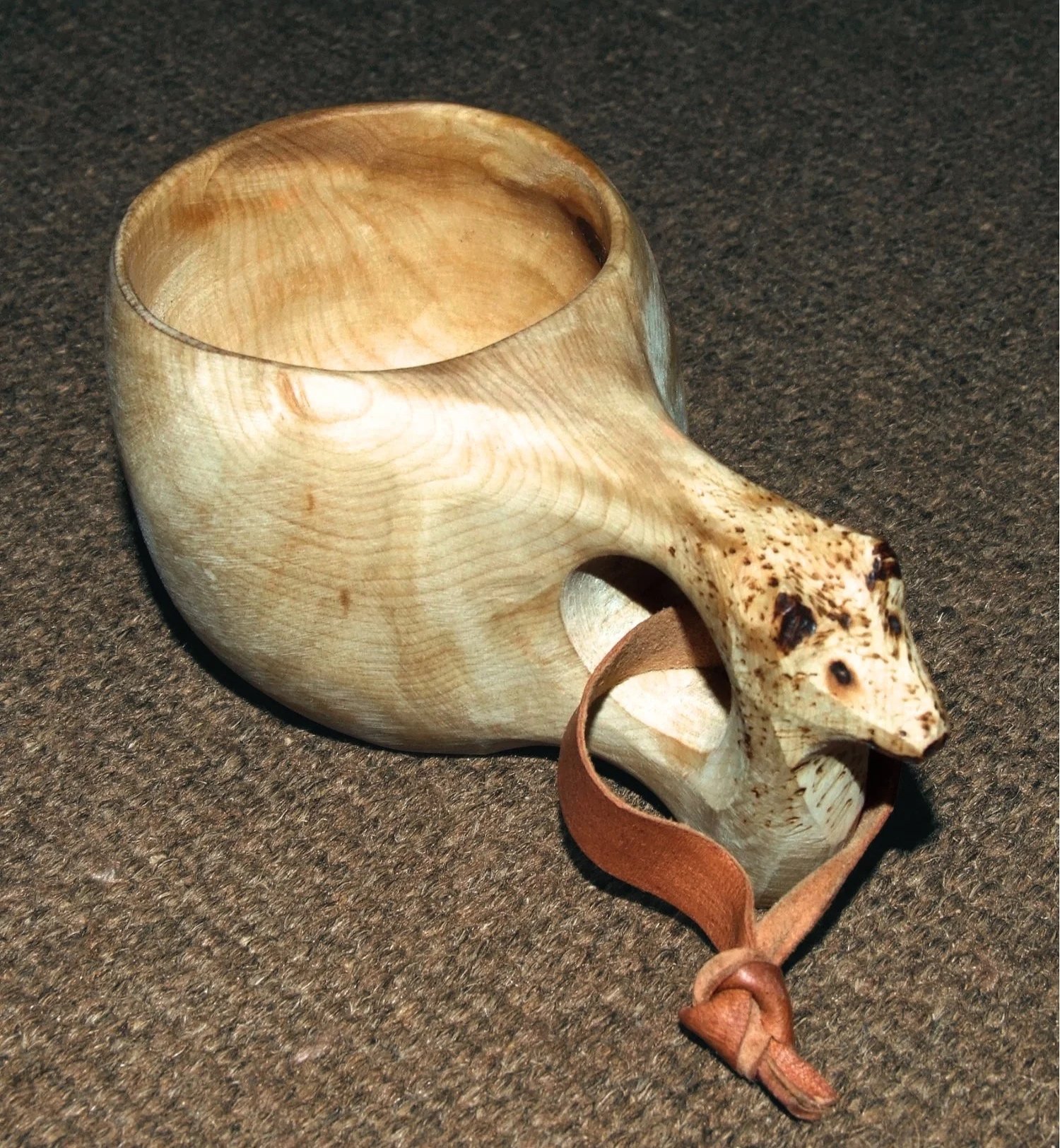

Carved Swedish kuksa - wooden cups carved from the burls of trees such as birches. Carvers intentionally embrace the irregularities of the wood - knots, twists and swirls - to give each cup a unique living character. Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons Jan 24. 2026.

A Shoki (鍾馗) mask used in kagura (神楽, shinto ritual ceremonial dance) in Shimane Prefecture, Japan. Historically carved from wood, these masks are considered to hold the spirit or presence of the deity (kami) they represent, particularly while in use during the performance. In Shinto, masks are often treated as sacred vessels (shintai) that the deity inhabits. Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons Jan 24 2026.

One quality of wood that sets it apart is wood’s voice remains visible and present, as agent and co-creator quietly shaping and influencing how the carver’s blade makes its mark through its grain, knots, texture. For this reason, wood encourages an especially intimate, embodied relationship between maker and material—a back-and-forth dialogue rather than a relationship of control. It may be for this reason that many ancient artisans and artists return to wood even when more durable, practical, cheaper materials are available—because its particular voice is a kindred presence and inspiring collaborator.

Other qualities of wood also contribute to the sense that carving it is a co-creation with a once-living being. In many cultures, wood was (and still is) understood as “alive”—the relationship between the carver and wood is seen as a conversation with ancestor or spirit of the tree. Wood is storied and safekeeps its own history in its rings, drought lines, and fire scars, recording years of growth, hardship, and survival, as well as marks and traces of dependent species of insects, birds and mammals within its body. In many cultures, carving a woodblock for printing was seen not simply as making an image, but as weaving one story into another. In some Asian traditions, woodblocks were believed to retain the breath of the carver, so that each printed image carries a trace of the original life force that shaped it. In Japan, the kami of the tree is believed to remain within the sculpture and the word for wood, ki (木), is pronounced identically to the word for spirit or energy - a linguistic connection that reveals wood’s ensouled qualities. Even in non-religious contexts, artisans often describe feeling “companioned” by wood. Wooden masks, idols, and ancestor figures have appeared throughout Africa, Oceania, Asia, and the Americas, shaped by the belief that wood can hold memory, breath, or presence. In Oceania, carvings are said to reveal the spirit already dwelling in the wood and in many European folk traditions, trees were and are believed to be inhabited by spirits or living presences, and woodworkers often treated their materials with reverence, suggesting that crafting wood was not just shaping matter but engaging with a tree’s enduring life force. In these contexts, wood was and is not only practical, but fabled and meaning-laden, its body a living record of its living journey through time.

A Yup’ik man on Nunivak Island, Alaska’s Bering Sea region, wearing a carved driftwood mask featuring a bird head adorned with feathers with hoops encircling the mask, known as ellanguaq ("pretend universe"), which represent the different levels of the universe (sky, sea, and earth). The mask serves as a form of prayer, intended to honor animal spirits—such as seals, walruses, and sea birds—and to ask that they would return in the spring to feed the human community. Photographed by Edward S Curtis early 20th century. Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons Jan 24 2026

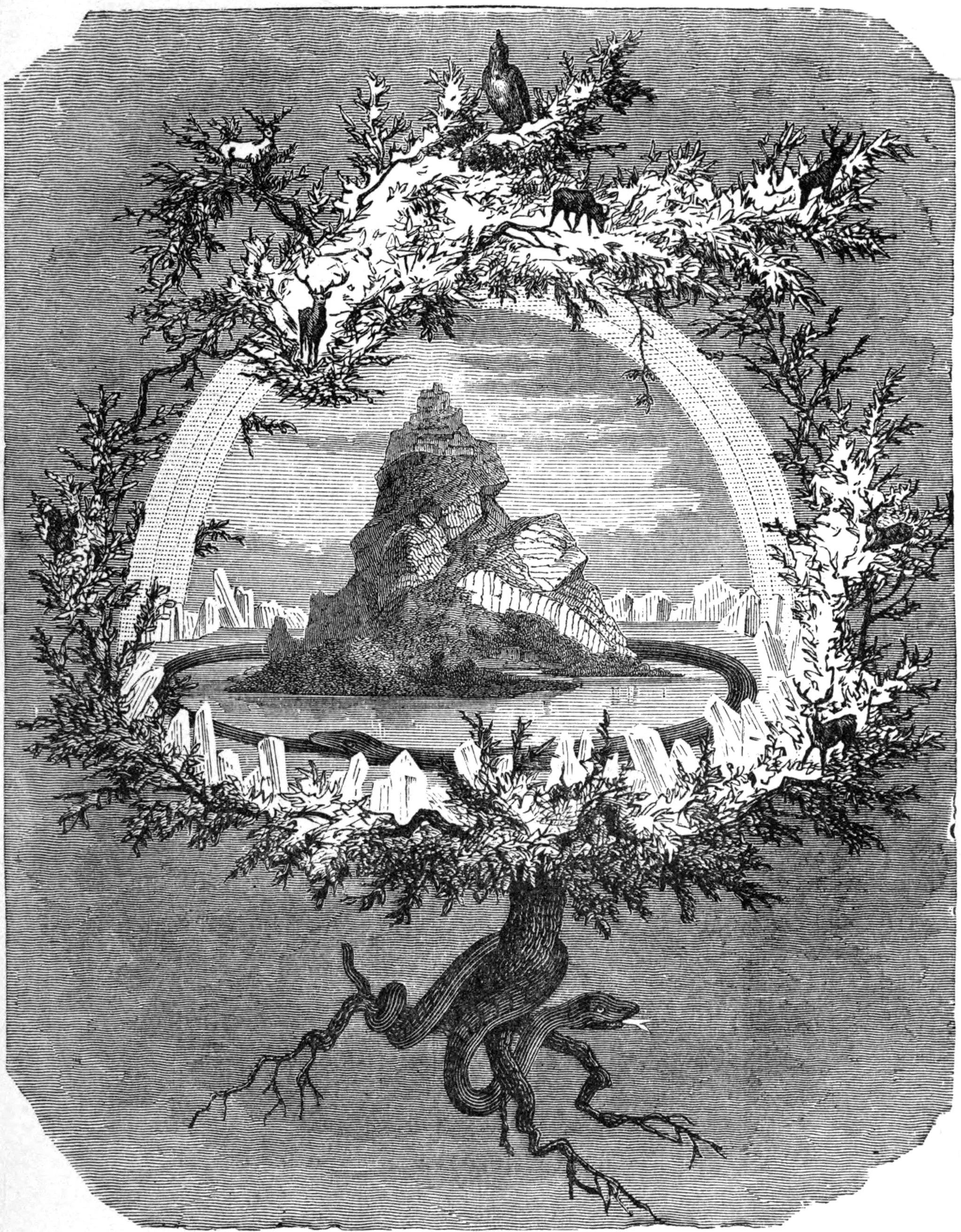

The Ash Tree Yggdrasil and some of its inhabitants 1886 created by Friedrich Wilhelm Heine, appears in Wilhelm Wagner’s book Asgard and the Gods. Image retrieved from Wikimedia Commons Jan 24, 2026.

Wood’s animacy and ensouled qualities is enhanced also by the ancient understanding that the tree itself if storied and spiritually potent —sometimes even a living pillar that joins earth and sky, the visible and the unseen. In folklore and cosmology, trees become what many traditions call the axis mundi: a central pillar through which realms are connected. In Norse myth, Yggdrasil, the great ash, binds together the Nine Worlds; in Maya cosmology, the Ceiba rises as a world tree connecting underworld, earth, and sky; and African traditions, the Baobab is revered as a "Tree of Life" for its vast lifespan and sustenance, acting as a spiritual center—each understood as a vertical axis through which worlds are held in relation.

Across many traditions, tree wood has carried this spiritual authority, serving as a medium through which the sacred can be repeated and dispersed. In woodblock printing—from Buddhist sutras and protective charms to mandalas and ancestral names—the image matters, but so does the material that bears it. The tree’s spirit is understood as participating in the act of repetition itself, so that each impression carries forward what the wood already holds. Ink, grain, and pressure forms a quiet ritual, allowing prayers and blessings to travel far beyond their point of origin. In this way, wood becomes both witness and carrier, holding the trace of hands, histories, and intentions as they move from one body into many.

In an age increasingly defined by acceleration and extraction, when forests and timber economies were under mounting pressure, wood’s slow growth and dwindling supply imposed temporal and logistical limits that quietly shaped the conditions in which artists and printmakers worked. Wood’s variable character—surfaces that resisted uniformity, grains that ran their own course—demanded patience, sustained attention, and continual negotiation, qualities misaligned with the rapid tempo of modern production. At the turn of the twentieth century, printmaking began to shift toward linoleum: inexpensive, widely available, and far easier to cut than wood, its smooth, grain-free surface supported fluid shapes and bold contrasts aligned with emerging modern aesthetics. At first glance, this shift from wood to linoleum may seem like a disruption and loss—from organic, storied material to something manufactured—but a closer look quietly reveals an underlying continuity, in which the material intelligence once found in wood reappears, reconfigured.

There is a subtle regenerative wonder in the making of linoleum, as discarded fragments of the natural world are gathered and joined into a unified whole. It begins with the gathering together of cork dust, wood flour, jute fibers, linseed resin—the quiet remnants of other plants, already lived with and used. Heated, pressed, oxidized, and bound together, these elements become a clay-like substance, spread onto a woven fabric—typically jute or hemp—where they settle into a new, cohesive material. Just as wood draws its strength from an internal network of cellulose fibers, holding together even as it is split, carved, or bent, linoleum too depends on a hidden lattice to endure. While oil, resin, and flour can bind naturally, the fibrous jute framework offers a kind of inner spine, lending strength and resilience; without it, the material would tear or crumble. In this quiet borrowing, linoleum carries forward something of wood’s unseen intelligence, reshaping it into a form suited to another time.

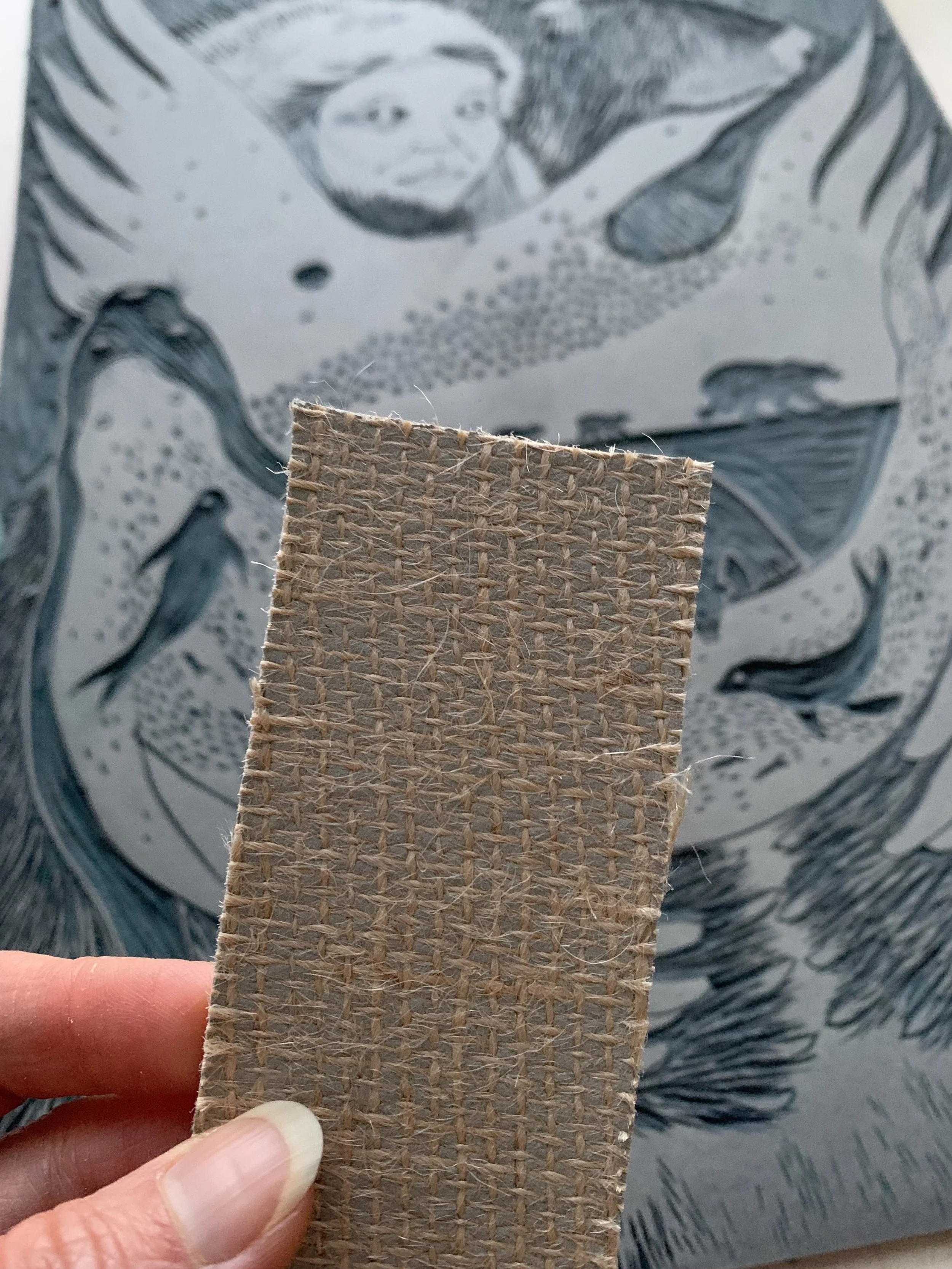

Details of a carved block of artist’s linoleum

Seen this way, linoleum is an equally storied material: its history is not of living growth, but the gathering of fragments discarded, ashlike, heated and reformed into something wholly new. The result is neither wood, nor cloth, nor resin, nor dust—but a new substance with its own character, There is a subtle magic here, a whisper of alchemy, in how heat and pressure, containment and joining turn the discarded into the serviceable, the ordinary into the receptive. Broken bits become whole, residues become surface, dust becomes design, plant remnants become vessel. In its making and in its use, linoleum reminds us how overlooked matter can be reborn into a material that is smooth, yielding, and equally ensouled.

One of the most beautifully symbolic aspects of linoleum is its woven jute backing—a “weaving” that serves as the archetypal feminine foundation for transformation. Even the word linoleum carries echoes of this layered, fibrous ancestry: coined in 1860 by English inventor Frederick Walton, it combines the Latin linum (“flax,” source of linseed oil) and oleum (“oil”), while its root linum also connects linguistically to the English words “line” and “linen”—threads, cords, and marks stretched across space. In alchemy, weaving imagery evokes the matrix, the vessel (vas), the holding environment, the body that receives and supports spirit. In lino, the jute performs this same function: it is the womb-like ground that holds the transformed material, while the lino compound becomes the skin or surface, and carving reveals form emerging through this supportive weave.

The woven backing of a block of linoleum

Just as early woodblock printers engaged with living wood, lino offers a modern surface that is organic, layered, woven, and transformable—a new prima materia for printmakers. Though it lacks wood’s knots, grains, and the long memory of growth and hardship, linoleum carries within its making a quiet alchemy of regeneration: composed of plant remnants, discarded flour, cork, and jute, it transforms what has fallen into a resilient, responsive surface. Wood speaks of creation; lino whispers of regeneration. Together they form a lineage of kinship, like sun and shadow, giving and receiving, creation and renewal. While modern artists may not yet speak of lino as “alive,” its organic roots and layered construction is already ensouled, and its surface can respond, remember, and carry forward what the artist breathes into it, if we learn to listen. In this sense, linocut is not a break from the lineage of woodblock printing, but a complementary evolution—a companion, a new material that invites us to see the magic hidden in what the world has left behind.

It is vital to acknowledge the socio-political and economic context that gave rise to linoleum: created in India under British colonial control, it was born within a system of extraction and oppression, inviting us to sit with its shadowed origins. Yet even amid such wounding and loss, traces of renewal and whispers of creation can emerge within this darker context. Today linoleum serves as resilient flooring in homes, schools, hospitals, and commercial spaces, and finds a place in art, printmaking, and occasionally in eco-conscious design for countertops, walls, and furniture. Though it can be sourced from renewable plant-based materials, and can be biodegradable at the end of its life, choices can affect its true sustainability. Nonetheless, I offer this meditation to propose a subtler way of seeing the relationship between ancient and modern worlds, often cast as opposed or in tension. What we see happening in the story of wood and linoleum is how even materials born of modern industry, traces of intelligence, responsiveness, and vitality remain, showing that connection between these worlds has potential to persist where we expect only separation.

Like the ancients, who believed a print carried the soul of its woodblock, I sometimes feel the carved linoleum holds the spirit of the image as well. Each time I bring it back to the table, roll ink across its surface, it wakes again—breathing, remembering, alive with the spirit of the tale. . ..

The story of wood and linoleum is a story of kindred spirits. One emerges directly from the living body of the tree, an ancient elder shaped by grain and time; the other a younger kin forged from gathered plant remnants—cork dust, wood flour, linseed resin pressed from flax, and a woven jute spine. One is carved from what once grew upright toward the sun; the other is born from what has been fallen, scattered, milled, pressed—fragments of many plants fused by heat and pressure into a new ensouled surface that still remembers its roots. Wood and linoleum share a lineage that echoes the folktale of the Weaver of the World, where tangled threads are rewoven and lost worlds reborn. In each, we see the same enduring truth: what has fallen can be remade, what has scattered can be rewoven into new whole. Reflecting on both wood and linoleum through storied eyes offers more than technical insight. It is an invitation to consider how carving wood or linoleum becomes a threshold moment where ordinary material hovers between the mundane and the meaningful, to carve them both is to participate in a quiet magic: the old alchemy in which humble matter is carved, the block awakens, new meanings emerge, and old ones are renewed. Through this unfolding, a timeless truth gently reveals itself: with every regeneration, the ancient art of creation survives, showing that the everyday world is never truly ordinary, but still hums with hidden seeds of enchantment and possibility.

References

“Axis Mundi.” Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia, Wikimedia Foundation, (en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Axis_mundi. Accessed 26 Jan. 2026).

Kwok, Castor. “The Whispers of Wood: How Japanese Artisans Capture the Soul of a Tree.” Oriental‑Artisan.com, 10 Aug. 2025, ( oriental‑artisan.com/blogs/knowledge/the‑whispers‑of‑wood‑how‑japanese‑artisans‑capture‑the‑soul‑of‑a‑tree. Accessed 26 Jan. 2026 )

Laffan, Julian “Locating Traces of Arboreal Beings: Connecting the Tree and the Woodblock” 24 June 2025 Archeology in Oceana. Vol 60. Issue 2. pp.145-155 (https://doi.org/10.1002/arco.70001Digital Object Identifier (DOI) Retrieved Saturday Jan 24, 2026)

“Linoleum” and “Woodcut”. Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., (www.britannica.com. Accessed 24 Jan. 2026 )

“Linoleum.” Online Etymology Dictionary, edited by Douglas Harper, (www.etymonline.com/word/linoleum. Accessed 24 Jan. 2026 ).

“The History of Wood Carving: From Ancient Craft to Modern Art.” Mokuomo, (www.mokuomo.com/blogs/blog/the-history-of-wood-carving-from-ancient-craft-to-modern-art. Accessed 26 Jan. 2026)

“What Is Linoleum?” The Flooring Group, (www.theflooringgroup.co.uk/what-is-linoleum/. Accessed 24 Jan. 2026 )

Across centuries, printmaking has evolved—tools shifting, surfaces reborn. At first glance, the move from wood to linoleum might seem a modern rupture, yet another story whispers through the fibers. Though one is an ancient elder growing upright towards the sun, the other a younger kin forged from what has fallen - scattered remnants of cork dust, wood flour, linseed oil, woven jute - they share a subtle kinship. What follows is a reflective exploration of how, beneath these differences, often cast as opposed or in tension, wood and linoleum echo the same material intelligence. They are related forms within a longer material lineage, binding tree to fiber, past to present, hand to spirit.