The cultural history and heritage of block printing is far more expansive—and enchanting—than I first imagined. What began as a simple inquiry for a single blog post soon opened my eyes to the vast and layered mythos, lore, and legacy of block printing: a soul-woven tradition where carved wood and pressed ink became sacred vessels for storied wisdom, spiritual protection, and cultural transmission across centuries and continents. Block printing’s mystique, its original devotional function as a keeper of sacred texts, divine myths and holy parables, and its profound role in shaping spiritual life throughout Asia - where it originated -reveals a tapestry so rich it calls for its own thread in my storytelling. So this post marks the beginning of a new series of blog posts centered around the mystical, material, and medial life of block printing. I hope you’ll wander the whiskered trail down the rabbit hole with me, all are welcome—curiouser hearts especially. A quiet pilgrimage and unforgettable adventure awaits where each step along the inked path reawakens old truths and forgotten magic.

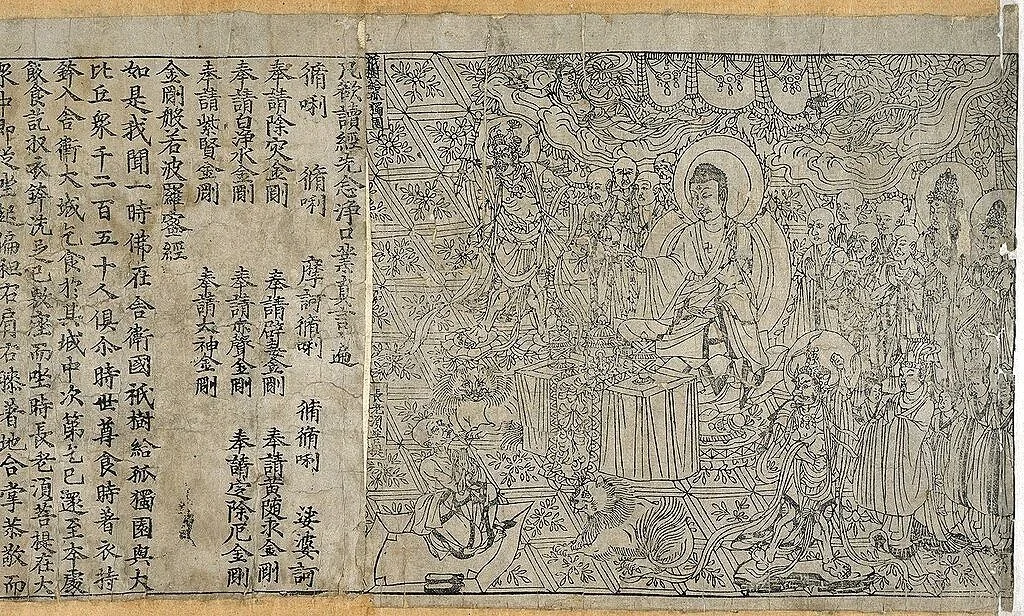

It was during the Tang dynasty (618–907 CE) in China that block printing first found breath and purpose, born to carry the sacred words of the Buddha—sutras and dhāraṇī, whispered spells of protection and light—pressed into paper like blessings etched in time. These sacred scrolls were more than written words; they were talismanic objects, often enshrined in temples or buried in stupas to guard both people and place. One early example, the “Great Spell of Unsullied Pure Light,” printed between 650–670 CE, was discovered in a tomb in Xi’an—a small yet powerful relic of devotion. Another remarkable discovery came in 1900, when a Daoist priest restoring a cave near Dunhuang uncovered a sealed chamber hidden for nearly 900 years, filled with thousands of sacred scrolls—among them, the Diamond Sutra, now recognized as the world’s oldest extant printed book. The Diamond Sutra explains how to cultivate prajñā (wisdom), the "diamond" that cuts through illusion by practicing generosity and compassion without attachment to self or results, ultimately leading to liberation from suffering.

The image depicts the frontispiece to the world's earliest dated printed book, the Chinese translation of the Buddhist text the Diamond Sutra. It consists of a scroll, over 16 feet long, made up of a long series of printed pages. Printed in China in 868 AD, it was found in the Dunhuang Caves in 1907, in the North Western province of Gansu. Photo Credit: Wikipedia Commons.

As Chinese block printing evolved from its early use in Tang dynasty Buddhist texts to broader cultural applications, it began to feature folklore, medicinal knowledge, and mythological figures—among them the beloved Jade Rabbit, a symbol of immortality linked to Buddhist themes and the Moon Goddess Chang’e. While the full archetypal trio of rabbit, moon, and goddess was passed down primarily through oral tradition and written texts rather than visual prints, the Jade Rabbit later emerged as a popular motif in Japanese woodblock art. This evolution highlights how Chinese block printing, even when not depicting the trio directly, served as a powerful vehicle for transmitting the myth’s core themes—its symbolism, wisdom, and Buddhist undertones—across cultures and generations.

As block printing spread from China, neighboring cultures adopted it also with spiritual intent. In the late 19th to early 20th century, during Japan’s Meiji period, hundreds of small 12th-century woodblock-printed images of the Buddha—each bearing rows of miniature seated figures—were discovered hidden inside the Amida statue at Jōruri‑ji Temple in Nara, likely placed there centuries earlier as acts of merit and spiritual devotion.

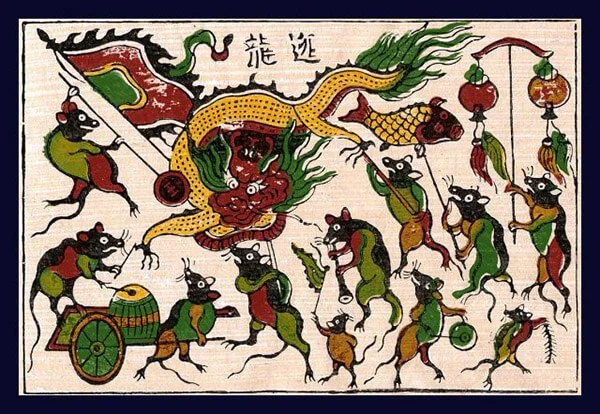

The Southeast Asia region, to the south of China, served as a crossroads for printmaking technology. In Vietnam, block printing flourished under monk Pháp Loa, who led the reproduction of the Tripiṭaka between 1295 and 1319. Stories tell of devotees mixing their blood with ink—a striking gesture of sacrifice and faith. The Đông Hồ woodcut tradition also emerged here, where local folklore and animistic beliefs, wisdom stories, folktales and scenes of ordinary country folk were block printed onto rice paper—bridging Buddhist devotion and everyday folk life.

Above: Carving tools and a woodblock at a Đông Hồ folk art blockprinting shop, Vietnam, which carries on this local tradition that dates back to the 11th century. Vietnamese Đông Hồ block prints depict local folklore, moral fables and scenes from the everyday life of ordinary country folk and are made with natural materials like tree bark, sea shells and natural pigments. See below for an example of a Đông Hồ block print of a local new year festival. Photo credit: Shutterstock.

Thailand’s gift to this sacred craft arrived later, woven deeply into the region’s living Buddhist manuscript traditions. Though early spiritual teachings were traditionally hand-copied onto palm leaves, the 19th-century printing of the Pāli Tipiṭaka—treasured scrolls of Theravada Buddhist wisdom—under King Rama I became a monumental spiritual act. More than mere scholarship, it was a ceremony of devotion which involved the participation of a thousand monks, and marked a shift toward block printing as a ritual act of transmission and reverence.

What unites all these examples is their shared understanding: block printing was not simply a tool of reproduction. It was a sacred vessel. These printed texts were not merely read; they were held, enshrined, and chanted. They became bridges between the human and the divine—objects of devotion, carriers of protection, and vessels of memory and belonging, reinforcing an enchantment with and voiced a recognition of the wisdom of the natural world.

A hand colored woodblock print of the Jūsambutsu-Mandala (Mandala of the Thirteen Buddhas), Muromachi period Japan 1336-1598. Photo credit: Wikipedia Commons.

The birth of block printing is where story and craft meet in sacred rhythm. Story is the yin: fluid, living, carried by voice and breath. Craft is the yang: deliberate, grounded, shaped by patient hands. Like lovers whose differences complete each other, they move in sacred tandem—a living current of spiritual truth passed hand to hand, heart to heart each reinforcing the other’s sacred intent. One is shaped from earth’s raw elements, the other from the sacred currents of timeless tale and together, they call the ancient voices back into living memory through ink and image.

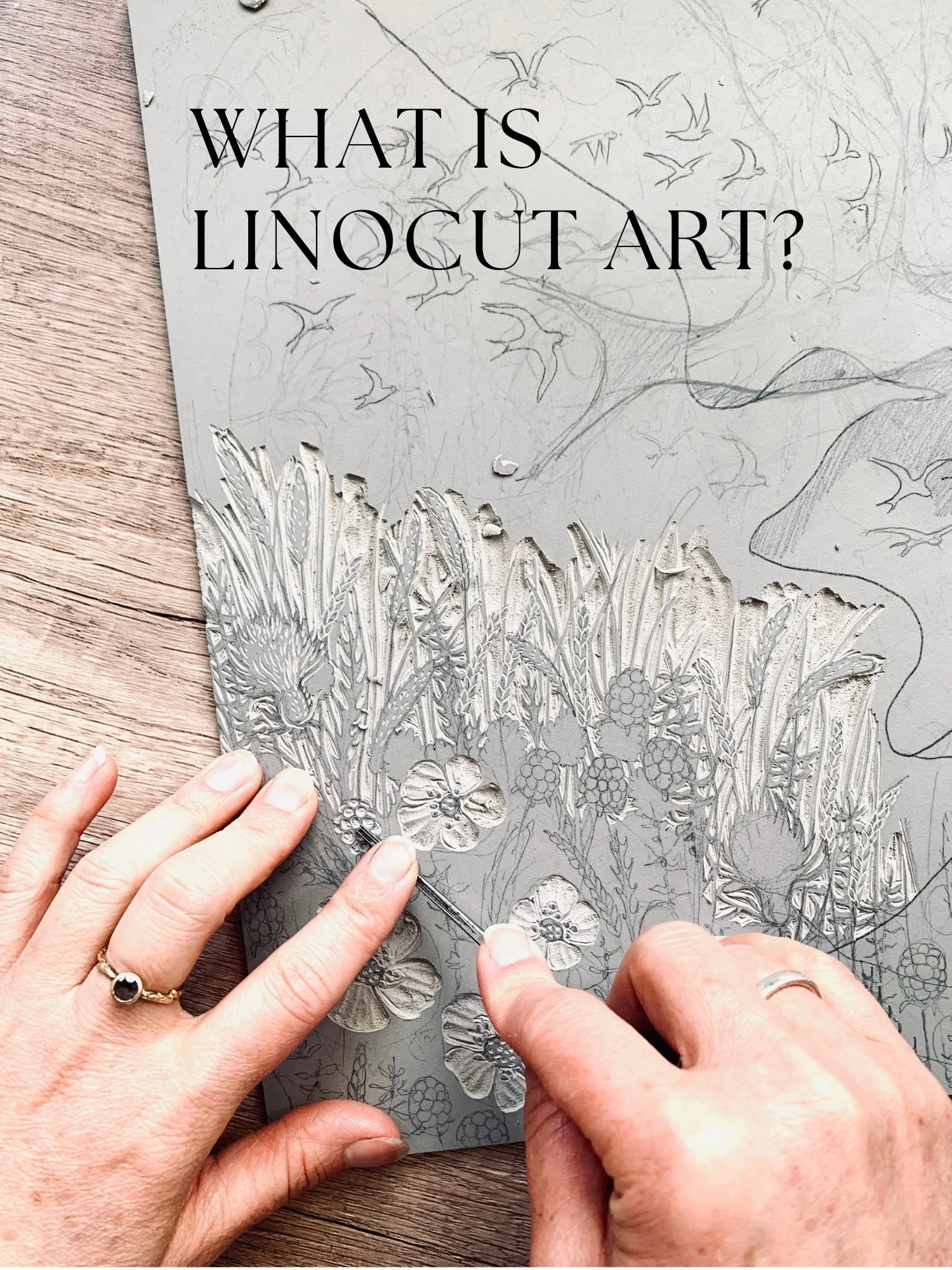

As a linocut printmaker working mostly in single colors, this act of tending to the balance between what is carved away and what remains, between light and dark, lies at the heart of printmaking design. This interplay mirrors the yin and yang of story and craft, echoing the ancient Taoist understanding that true wisdom arises from the dance of opposites—where visual form and deeper meaning move in rhythm, each giving life to the other. What moves me most is how this principle of harmony through contrast is not only central to Taoism, but also deeply resonant with the Buddhist concept of nonduality. In Mahayana and Vajrayana traditions, opposites such as form and emptiness, self and other, samsara and nirvana are understood not as contradictions, but as interdependent and ultimately inseparable. In Zen, nonduality is explored through direct experience, where the dissolution of dualistic thinking becomes a path to awakening. In this way, the practice of printmaking becomes more than a craft—it becomes a quiet meditation on nonduality itself: a tangible meeting place where what is removed and what remains co-create meaning. Passed from hand to hand through the steady rhythm of generations, I feel honored to be part of that lineage, where each cut and impression echoes a deeper unity.

Here are photos showing the carving, printing, and design process behind The Weaver linocut. I intentionally played with printmaking’s signature interplay of positive and negative space to echo the essence of Yin and Yang. The moon phases and drifting white dandelion seeds reflect the light within the dark, while the crows and tangled botanicals in the old woman’s white hair evoke the dark within the light. Crow feather earrings and her placement within the "cave" of the crow further weave together the folktale’s deeper message: that creation and destruction are not opposites, but intertwined—each feeding the life of the other.

Woven into this history, too, is the truth that the dispersal of block prints and the Buddhist teachings they carries to many landscapes was a wellspring that nourished a collective awakening in a world divided by caste and hierarchy, whispering to the forgotten that they belonged. For this reason the history of block printing is not only devotional but defiant—a quiet ritual of resistance carrying radical truths older than empire and power that refused to be erased. Carved into ancient wood and pressed onto fragile paper, these teachings transformed into talismans of defiance, carrying the eternal flame of nonviolence and freedom for all through the darkest of times.

As the ages turned, this sacred craft kept its spirit of resistance alive, preserving the voices of those who dared to dream. In 13th-century Korea, for example, when Mongol invaders destroyed the original Tripiṭaka Koreana, the Goryeo dynasty responded not with surrender but with spiritual and cultural defiance—commissioning a second, flawless recreation of the entire Buddhist canon across more than 80,000 woodblocks, carved meticulously over twelve years as a profound act of national protection and devotional renewal. In 8th-century Japan, amid political turmoil Empress Shōtoku commissioned the mass production of the Hyakumantō Darani—one million miniature wooden pagodas, each housing a printed dhāraṇī scroll—as both a devotional act to strengthen her authority and restore order across her realm. And in Vietnam, Đông Hồ Village used to be the center of politics and culture of Northern Vietnam, and Đông Hồ block prints were a medium used to subtly express social, political, and cultural criticism including anti-colonial ideas during French colonial occupation.

These stories whisper of block printing’s enduring role—not only as a vessel of spiritual wisdom, but as a shield of resilience and a song of defiance. Centuries after its sacred beginnings, block printing journeyed along the Silk Road, eventually helping to place the power of the written word into the hands of ordinary people—awakening a quiet revolution where knowledge, once reserved for the elite, became a tool of resistance against oppressive forces.

For me, carving an ancient tale into ink and paper is not only a continuation of the sacred bond between storytelling, sacred wisdom and block printing that first birthed this art form—it’s a vital act of remembrance. In each print, I honor an old rhythm where craft and devotional myth move as one, and where creation becomes both offering and invocation. This union of opposites—form and fluidity, light and shadow, voice and silence—is more than aesthetic; it is an ancient archetype, a living wisdom that teaches us how to hold tension without collapsing into division. In a world increasingly fractured by black-and-white thinking, this practice becomes an act of resistance and renewal. The printmaker’s sacred ritual of balancing what is carved away with what remains—shaping story from absence and form—is a way of actively tending the medial thread held by the Old Weaver as she works the loom between cauldron and crow. In everyday life we, too, are called to hold that thread—if we are to step wisely into the next turning of the great tale.

This is Old Story Medicine, rising again—inked and alive.

References:

Le Thuy Hang, & Vu Hong V. (2020). Method of printing carved on wood under the Nguyen Dynasty of Vietnam: Study of woodblocks recognized by UNESCO as a world documentary heritage. International Journal of Psychosocial Rehabilitation, 24(6). Retrieved Aug 30.2025.

McArthur, M. (2014, October 17). Printed prayers: Japan’s first woodblock-printed Buddhas. Buddhistdoor Global. Retrieved August 30, 2025.

Metropolitan Museum of Art. (n.d.). One of the “One Million Pagodas” (Hyakumantō) and Invocation [Object number 30.47a–c]. In The Metropolitan Museum of Art Collection. Retrieved August 30, 2025.

Norman, J. (2025, June 11). The Diamond Sutra, the earliest surviving dated complete printed book. History of Information. Retrieved August 30, 2025

Paradowski, R. J. (2022). First book printed. EBSCO Research Starters. Retrieved August 30, 2025.

Planète Corée. (n.d.). The history of foreign invasions in Korea. Planète Corée. Retrieved August 30, 2025.

Princeton University Art Museum. (n.d.). Cassia Tree and Jade Rabbit (object no. 17563). Retrieved August 31, 2025, from Princeton University Art Museum collections website.

Saddhatissa, V. H. (n.d.). The advent of Pali literature in Thailand. Buddha Sasana. Retrieved August 30, 2025.

Viewing Japanese Prints. (n.d.). Beginnings of Japanese woodblock prints. ViewingJapanesePrints.net. Retrieved August 30, 2025.

Wolfson‑Ford, R. (2021, June 22). The history of printing in Asia according to Library of Congress Asian Collections – Part 1. 4 Corners of the World: International Collections at the Library of Congress. Retrieved August 30, 2025.

Zhu, Y. (2025, July 25). Ink, wood and wisdom: The legacy of Chinese engraved block printing. City News Service. Retrieved August 30, 2025.

What weaves its way like an underground warren beneath the borders of conquest and control, preserving our collective wild sisterhood with the earth across time, cultures and landscapes? The ancient link between hares, the divine feminine, and the moon journeyed from Asia to the Americas—carried by storytellers, pilgrims, healers, and wanderers. What might we reclaim if we traced their sacred steps?