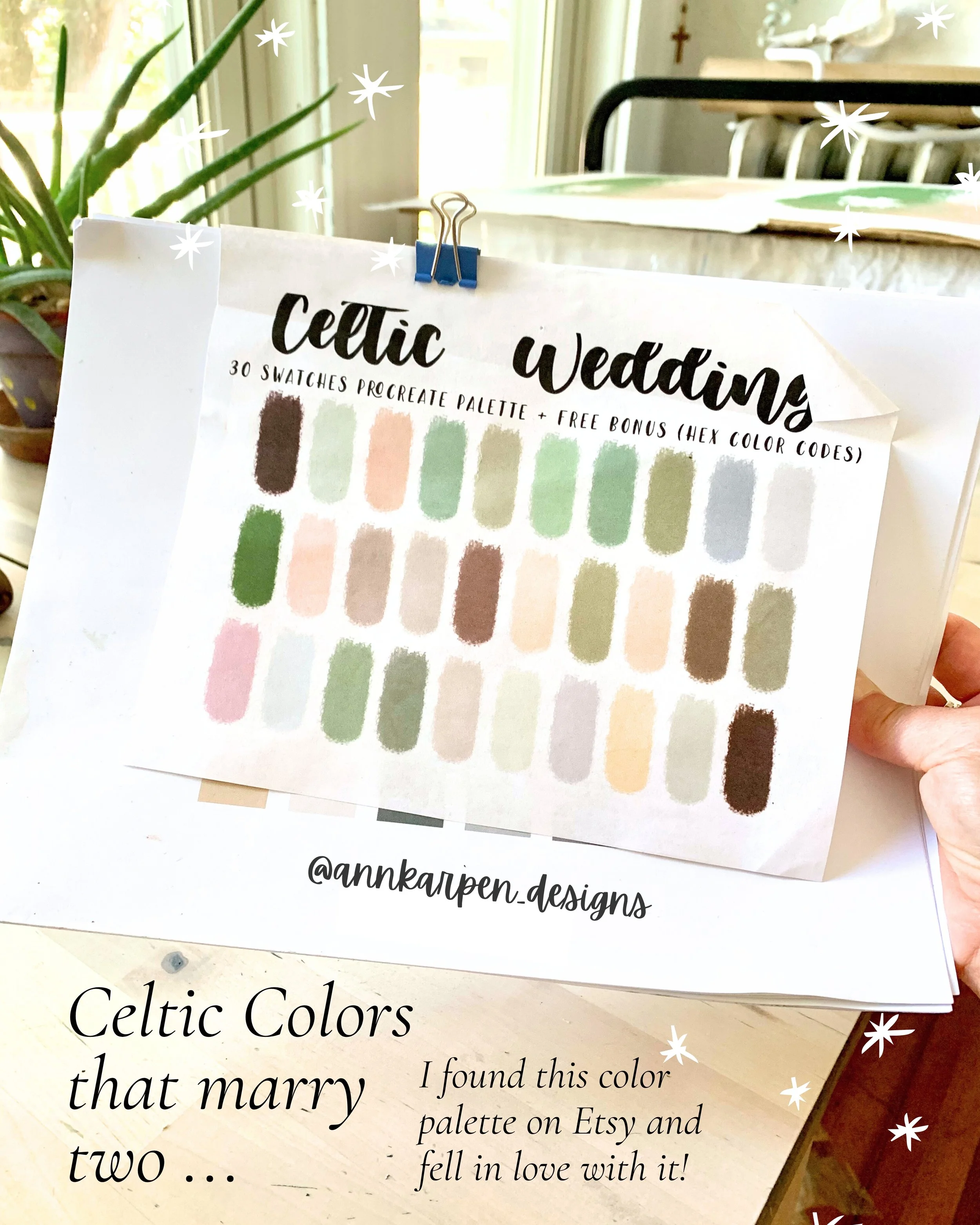

Figuring out the color combinations for this new linocut inspired by Celtic horse goddess myths.

How do we live with the parts of ourselves that seem to gallop in opposite directions—one pulled toward duty, the other aching toward desire? How do we bear the unbearable sorrow of the world alongside its wild beauty, or honor the delicate balance between tending to others and remaining true to our own wild calling?

Myth doesn’t give us neat answers, but offers meaning, metaphor, and creative possibilities in response to our questions. Woven into the heartbeat of Celtic horse myths is a golden thread of this untamed wisdom—a teaching on how to live within paradox. These stories contend with the same complex terrain we do: they light the path between the ache of what feels unresolvable and the resolution buried deep, waiting to be found.

In Courting the Wild Twin, mythologist and storyteller Martin Shaw recounts the Celtic legend of Cú Chulainn, a warrior bound to two wild horses—one a grey mare, the other a black stallion—said to have risen from a lake, otherworldly, magical, and utterly unbreakable. Each horse pulls him in a different direction, threatening to tear him apart. But the true hero, according to legend, is not the one who conquers or escapes the tension—but the one who can hold both. Cú Chulainn alone can ride the space between without forcing resolution, and in doing so, wins the trust of the two steeds - named Liath Macha and Dub Sainglend—who become his loyal companions for life. Shaw reminds us this story does not celebrate physical strength or conquest, but is honoring the deeper art of balance—of holding tension without collapse, and navigating the threshold where opposites meet. He speaks to how ancient stories like this one illuminate the paradoxes we all face in life: the pull between instinct and intellect, wildness and duty, shadow and light. Too often, we feel pressured or compelled to ride only one horse—choosing control over surrender, or reason over feeling—leaving the other behind. But Shaw suggests the tale of Cú Chulainn calls us to something braver: to reconcile with our wild twin, that exiled, instinctual self we’ve cast out in the effort to avoid the complexity and discomfort of holding the tension between two opposing things. In learning to hold the reins of both truths, we awaken what has long slept in shadow—and with it, a deeper sense of wholeness, and purpose, we become the hero or heroine in our own story, braided and born from the tension itself.

Before offering my own perspective, I must first acknowledge this humble note: I am not a scholar of Celtic mythology. I am just an artist and curious soul, pulled by the wild heartbeat of myths, folktales, and folklore that inspire my linocut print designs. I do not claim mastery or ownership—only a deep personal resonance with the wisdom and gifts these tales offer me. My words below arise from my own personal relationship to the stories, and it is with that spirit of reverence, wonder, and open-hearted inquiry that I offer them.

It seems that on the surface, the myth of Cú Chulainn may appear to center around a male hero, but it opens beautifully into the feminine realm when we consider the rich tradition of horse goddesses in Celtic folklore*. In Celtic tradition women are closely tied to wild horses—not just as riders, but as living symbols of sovereignty, wild grace, and the deep, transformative spirit of the horse itself. In fact horses weren’t simply seen as animals to be tamed, but as spiritual companions, mirrors of the human soul, sometimes even revealing what lies beneath and guiding us toward healing and wholeness. Approaching the myth of Cú Chulainn through this lens reveals a dance between the masculine and feminine—not one of domination, but of dynamic partnership. It also suggests that the struggle between rider and horse is not merely physical, but a soulful, psychological struggle between forces within the Self.

In this way, the following Celtic horse goddess myths begin to feel less like distant relics and more like living voices—whispering through time, offering insights into our own souls and the timeless struggles of the human experience. Their wisdom speaks to our contemporary conundrums, offering a kind of medicine for modern-day wounds.

Among these living voices from the past, none rides with more mystery and quiet power than Rhiannon, Celtic horse goddess written of in the Welsh Mabinogion, a collection of medieval tales drawn from oral tradition and one of the most important sources of Celtic mythology and early Arthurian legend. Rhiannon rides through legend on a white horse no man can catch, her beauty woven from the threads of the Otherworld—graceful, glimmering, always just out of reach. Choosing her own husband and defying convention, she is an image of sovereign will, yet she is later accused of murdering her own child and is punished with deep humiliation. She moves from queen to accused, from honored to humiliated—holding sovereignty and subjugation within the same mythic arc. She also is associated with the cyclical nature of the moon, which is fitting considering that she holds the balance between new moon and full moon and all the interations in between. Rhiannon’s association with enchanted horses positions her as both divine and deeply human—an ethereal being who must endure earthly injustice. Her story does not resolve its tensions; instead, she holds them, dignifies them. She doesn’t escape contradiction—she fiercely rides it.

If Rhiannon rides the wind between worlds, the Celtic horse goddess Macha from Ireland thunders across the earth itself—her hooves striking sparks where body and spirit meet. Macha** is an emblem of paradox - where the womb meets the battlefield, and sorrow strides beside sovereignty. In one of her most haunting legends, she is forced to race against the king’s horses while heavily pregnant—and she wins. But at the finish line, she collapses to her knees and gives birth to twins—pain and triumph braided into a single breath. She does not simply run the race; she becomes the very ground it is run upon, her body echoing through the land now known as Emain Macha, or “Macha’s Twins.” Both cradle and battlefield, this sacred site holds the memory of how this horse heroine rides the edges of what the world insists must be kept apart, weaving together what is broken and naming it whole. It is said she gifted the grey mare Liath Macha to the warrior Cú Chulainn—a horse born of her spirit, carrying forward the untamed balance of her legacy.

Next comes the Celtic goddess Epona, known as The Great Mare, who also stands at the crossroads of opposites: harvest and warfare, womb and underworld, sovereignty and servitude—cradling both the fruits of the earth and the weight of the spear, guiding kings in life and souls in death. In one hand, she carries a cornucopia overflowing with harvest; in the other, a shield or spear. She cradles the fruits of the earth and the weight of war in the same body. Often depicted flanked by horses and foals—symbols of kingship, fertility, and sacred power—Epona is more than a goddess of horses; she is a guide between realms, leading both kings in life and souls in death. Her name, derived from the Gaulish epos (horse) and the feminine suffix -ona, speaks to her elemental nature: she is not merely associated with the horse—she is the living force that holds the balance between power and peace, sovereignty and surrender. So beloved was she that her worship crossed tribal lines and national borders, adopted into the Roman pantheon and revered across the empire, especially by cavalrymen who trusted her to carry them between the seen and unseen. Epona endures as an ancient reminder that true sovereignty is not about control, but about the quiet strength to stand where opposites meet and not turn away.

And then there is Étaín—who doesn’t gallop into legend, but drifts through it like mist, like memory, like a dream half-remembered. Étaín’s tale of love, loss, and transformation is engraved in the ancient saga Tochmarc Étaíne, an important mythological tale from early Irish literature. Born a radiant maiden, Étaín is caught in a web of jealousy and sorcery that drives her through a series of rebirths—transformed first into a pool of water, then into a worm, then a butterfly, drifting on the wind and living for centuries unseen. As a butterfly, she is finally swallowed in a cup of wine and reborn once more as a human—her spirit carrying the memory of all she has passed through. Étaín’s story, at its heart, is one of exile and return, the pain of separation, and the elusive quest for belonging and identity. Her epithet Echraide, which means “horse-rider,” is more than a title—it is a metaphor for her restless spirit, caught between worlds and cycles of life untamed and unbound. Unlike myths that place a heroine firmly in the saddle, Étaín’s horsewomanship is symbolic—she journeys on the back of currents of transformation itself evoking her kinship with the untamed, threshold-crossing force of the horse. Her story pulses with the rhythm of the wild mare—sovereign, cyclical, and unpossessable—moving between worlds with grace and mystery. Like the horse goddesses Rhiannon, Epona and Macha, Étaín is a liminal being: a guide between realms, a vessel of sovereignty, and a mirror of the soul's longing for return. Beneath her many metamorphoses lies the solitary strength of an untamed steed—one who does not merely cross boundaries, but dissolves them entirely.

All four Celtic horse goddesses—Rhiannon, Macha, Epona and Etain—are luminous figures who do not erase the contradictions within their stories; they hold them fiercely braided together, riding the tension between nurture and command, grace and wildness, exile and belonging. They do not gallop towards simple answers, their stories remind us wholeness is not found in resolution, but invite us to see that life’s deepest challenges—grief and joy, loss and renewal, power and vulnerability—are not opposing forces to conquer, but interwoven threads of a single tapestry. The beauty and power of their stories lies not in their perfection, but in how they carry contradiction like a crown. What lingers in the heart is not their certainty, but the tender way they inhabit the questions—braided, broken, and whole.

To deepen the full mystery of these horse goddesses, it is essential to honor the reality that in ancient times the domesticated horse has frequently stood as a living symbol of prestige, power, and sovereignty—its pounding hooves marking the rise of empires and the forging of legends. From the windswept moors of Ireland to the vast steppes of Central Asia to the royal courts of Europe, domesticated horses bore the burdens of battle, trade, and harvest, linking rulers to their dominion over land and people.

First print. . .at this point in the process I realized something more needs to be added and the colors need to be changed.

In a parallel way, women in many landscapes were once also bartered, bound, and prized for what they could offer to power: alliances, heirs, and the preservation of legacy. When the balance tipped toward the rule of kings over queens, and the old ways of the mother were overrun by the laws of men, history reveals a recurring pattern where a woman’s worth was measured less by her wildness and more by her submission. Yet in both horse and woman lives a shared, ancestral longing—for a life not possessed, but chosen; not harnessed, but wholly lived. The flowing mane of a horse, like a woman’s unbound hair, has long been a symbol of beauty, freedom, and elemental power—a banner of the untamed Self.

Through the telling of these Celtic horse goddess myths, we glimpse echoes of a time when feminine power was not peripheral, but central—woven into the fabric of land, kinship, and sovereignty. Whether these stories arose from memory, longing, or resistance, they carry the imprint of a world where horses and women were not yet broken to the yoke of ownership. Their wildness remains intact in myth, unbridled and luminous - a call to remember what was, what was lost, and what might still be reclaimed.

Celtic horse myths speak of a power older than conquest—one that refuses the rigid hierarchies of empires. This is not the force of dominion, but the strength to live in paradox: to be rooted yet roaming, tethered yet untamed. Cú Chulainn’s bond with his horses reflects this power beautifully—not as mastery, but as mutual recognition. His steeds are not broken into obedience; they remain wild, willful, and free, offering their loyalty not through fear, but through trust earned in respect. In their mirrored movement, we glimpse a deeper rhythm of power—one born not from control, but from communion.

The final print. The Goddess Rhiannon is associated with an ethereal white horse, song birds and the moon.

This dynamic tension between opposing forces is not unique to Celtic legend. It pulses through many ancient spiritual traditions across the world. In Taoism, the balance of yin and yang teaches that harmony arises not by choosing one side over the other, but by honoring the relationship between the two. The Tao Te Ching describes the Tao—the “Way”—as a mysterious, ungraspable force, much like wild horses, that resists domination and instead invites us to move in rhythm with life rather than against it. Similarly, Hindu Tantric cosmology reveals the sacred complementarity of Shiva and Shakti—stillness and motion, consciousness and energy held in divine union. Buddhism’s Middle Way offers a path between extremes, inviting us to embrace complexity without collapse, cycling through forms and experiences without clinging to fixed identity. All of these traditions show us how to live in tension, riding the space between, toward healing, wholeness, and connection.

The wisdom of Celtic Horse mythology is that to endure, to trust, and to carry complexity with grace is its own kind of sovereignty. This sovereignty is not rigid control or absolute mastery, but a wild freedom that flows effortlessly between worlds. It moves with the rhythms of nature—the waxing and waning moon guiding Rhiannon through her phases; the fierce Macha riding the storm between womb and war, torment and triumph; Epona guarding both bounty and bloodshed; and Étaín, ever-shifting, wearing many forms like a cloak woven of light and shadow. True power is a rhythm we live: a sacred dance between holding and letting go, between honoring our wildness and choosing when to yield. The horse is not a possession in these stories, but a mirror of the Self and soul—unbridled, luminous, and deeply free.

Notes

*Some say Liath Macha (meaning “Macha’s Gray”), the name of one of Cú Chulainn’s two chariot horses, suggests a symbolic link to the Celtic horse goddess Macha.

**Macha is one of the three sisters who make up the Morrígna, often collectively referred to as The Morrígan—a powerful trio of war and sovereignty goddesses in Irish mythology. As a triad, they often appear before or during battle to foretell doom or rally warriors, tying the fate of men to the power of the land and the women who personify it.

References, Storykeepers, and Sources:

MacKillop, J. (2004). Dictionary of Celtic Mythology. Oxford University Press.

McCormick, A. von R., McCormick, M. D., & McCormick, T. E. (2004). Horses and the Mystical Path: The Celtic Way of Expanding the Human Soul. New World Library.

Shaw, M. (2022). Courting the Wild Twin [Audiobook]. Audible Studios.

With deep gratitude to the mythkeepers, scholars, storytellers, and ancestors whose words, wisdom, and wonder helped guide this journey. This offering is a tribute, not a claim—a way of honoring the living stories that continue to gallop through our hearts and histories.

What weaves its way like an underground warren beneath the borders of conquest and control, preserving our collective wild sisterhood with the earth across time, cultures and landscapes? The ancient link between hares, the divine feminine, and the moon journeyed from Asia to the Americas—carried by storytellers, pilgrims, healers, and wanderers. What might we reclaim if we traced their sacred steps?