Who can resist the mischievous charm of the timeless trickster, Puss in Boots? Though the tale first appeared in Italian folklore, the most well-known version comes from French writer Charles Perrault, who published Le Maître Chat, ou le Chat Botté ("The Master Cat, or The Booted Cat") in 1697. In Perrault’s version, a clever cat uses cunning and deception to transform his poor master’s fortunes, even securing him a royal marriage. While many children have long enjoyed the original tale, Puss in Boots truly became a household name only after his animated debut in Shrek 2 (2004), voiced by Antonio Banderas.

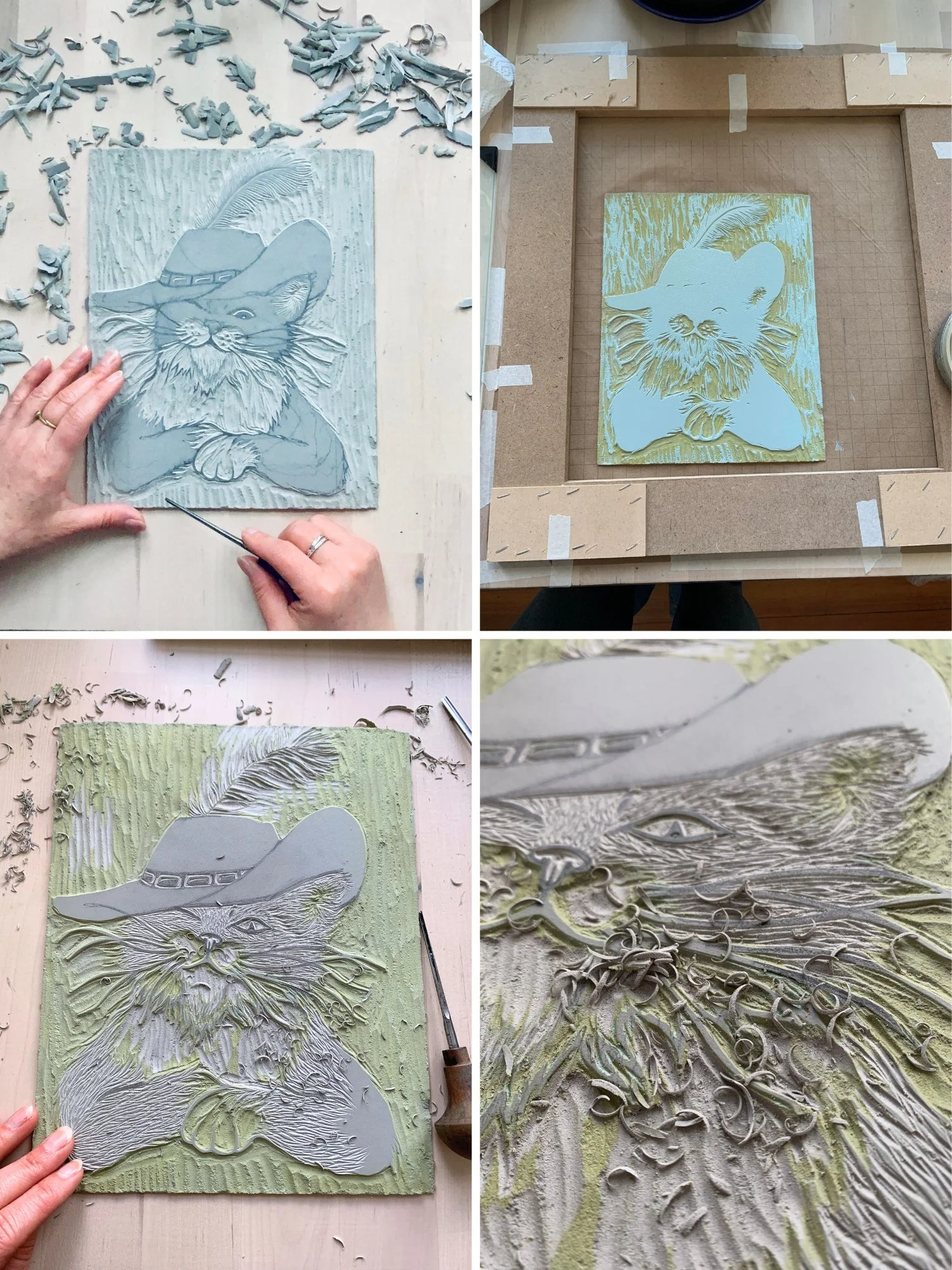

The beginning stages of carving

Almost overnight, this charming, sword-wielding feline became a fan favorite. He went on to appear in several Shrek sequels, eventually starring in his own films—Puss in Boots (2011) and Puss in Boots: The Last Wish (2022)—which catapulted him to global fame. DreamWorks further expanded his universe with various animated shorts and television series, building an entire mythos around the character. Audiences who may never have encountered the original tale were captivated by this adorable mischievous outlaw always ready to stand up for the underdog and answer the call to heroism. Though the films stray far from Perrault’s version—blending elements from multiple fairytales into a single cinematic world—the spirit of Puss in Boots remains unmistakable. He still stands as the quintessential whiskered trickster, using wit, charm, and courage to overcome the odds. And in doing so, he continues to warm and inspire modern hearts.

Reflecting on the rising popularity of Puss in Boots through his reinvention in comedic action animation feels timely and meaningful. His story offers a vivid example of how a classic folktale can be reshaped to capture the imagination of new audiences. In the world of folktale and fairytale enthusiasts, I've often witnessed lively—and sometimes tense—conversations around this very issue: Should we preserve ancient stories exactly as they were first told, or do we have the right to reimagine them for our own time? Some believe that the original versions alone hold the deepest value, insight, and spirit of the tale. Others see retellings as a vital part of keeping stories alive—allowing them to evolve and remain resonant across generations. In the following paragraphs, I share my reflections on this ongoing debate and suggest ways we might navigate the space between honoring tradition and embracing transformation.

I have a disclaimer: I am not neutral on this issue, and yet while my own perspective on this will naturally come through (perhaps it has already!), I offer it recognizing that this is a complex, layered terrain. My hope is to offer a few threads that might sit alongside your own reflections as we each consider how to navigate this evolving dialogue.

These series of photos show the process of creating a reduction linocut. Top two photos: A block of linoleum is carved to make a first print. Bottom two photos: Then the same block is carved more to print on top of the first.

When thinking about an ancient story, the tendency is often to regard the past as something set in stone—permanently unchangeable—a concept more like a noun rather than a verb. I love how the word lineage unravels and reframes this very idea. Derived from the Latin linea, meaning string or thread, lineage invites the metaphor of weaving—suggesting an act of stitching past and present together along a continuous thread. The concept of heritage, rooted in the Latin hereditare, meaning to inherit, also comes to mind when thinking about ancient stories. Heritage reflects the transmission of something valuable passed down through the collective family of culture—whether tangible, like a sacred monument or architecture, or intangible, like a shared relationship to the land, communal rituals, celebrations, values, and stories. Finally, the word heirloom—with roots in both heredity and heir (from Anglo-French), and loom (Old English)—ties heritage and lineage together. It suggests that the past and the present are not only woven together, but that history itself is woven on a loom, and that remembering is the very act of tying together what was and what is.

The concepts of lineage, heritage and heirloom together evoke not only a living breathing thread of wovenness of past and present, but also the intimate, living relationship between ancestor and descendant, coming close to the metaphor of parent and child. Like a child who carries the essence of their lineage yet grows into someone wholly their own, I believe a story endures not by remaining fixed, but by evolving. A loving relationship—whether between parent and child or between an original story and its modern-day teller—honors transformation not as a loss, but as the very path through which the child becomes themselves, and the story finds a way to live on in different times and landscapes. In this act of surrendering to change, stories live longer, journey farther, speak to more hearts than they ever could if they stayed fixed in place. Letting a story change isn’t a betrayal of its roots—it’s an honoring of them, as we see in the journey of Puss in Boots.

We can see examples of this story transformation taking place in the folkloric trio of hare, moon and divine feminine which originated in East Asia and traveled the Silk Road taking on new meanings as it made its way all the way to Europe. We see can also this manifested in the many iterations of Fox Woman throughout the globe.

This living transmission—woven through time like a tapestry of kinship between elders and descendants—lies at the heart of the folktale tradition: where the original story is held with reverence even as a new version is born through each generation. Each new teller of an old tale becomes both guardian and creator, adding their voice to a long lineage of voices, so that the story becomes not a relic, but a shared creation—alive, evolving, and ever becoming.

Its easy to overlook, but vital to remember that some ancient stories are themselves shifting even in their original state. Caribou herding cultures that circled the northern hemisphere of the world include folktales that reveal how human identity was forged around an intimate relationship with caribou and a fidelity to their migration over a landscape rather than identifying with a single location. Through these caribou stories’ shared similarities, we discover landscapes we now think of as separate countries woven together, quietly challenging how we define “origin,” suggesting instead that movement and change itself may be a form of deep belonging and honoring of the spirit, heritage and lineage of an original story.

But stories, like all living things, grow with a twin shadow at their feet, and this is where complexity arises. Sometimes, stories are changed not out of reverence or natural evolution, but as tools of control, erasure, or domination. This often happens through colonialism, war, or forced assimilation—when the stories of a people are deliberately altered or silenced in order to erase their identity and replace them with the values and voices of a dominant culture. In these cases, the story doesn’t evolve as part of its organic survival and thriving over time—it is overwritten or erased as a means of enforcing sameness and loyalty to the oppressive power. That’s why it’s so important to discern how and why a story is changing and the true intention of the storyteller. Is the story being reshaped as an act of continuity and tribute—as in the case of Puss in Boots, where the spirit of the original trickster folk-hero is still alive and thriving in his animated modern form? Or is the change a tool of cultural erasure, where the story’s roots are forgotten or erased or twisted in the service of those striving for power at the sacrifice of and erasure of others? (I think in many cases it may truthfully be a complex combination of both these things - it is difficult to separate the shadow from its twin).

What follows are a couple of blog posts where I’ve explored the layered terrain of how stories can be buried, silenced, or marginalized—and also how they can shift in ways that resist oppression and offer voice to what has long gone unnamed and forgotten. In Carving Memory, Gathering Bones, Singing Her I cover how some ancient stories can be buried like bones, and how excavating them and singing over them to bring them back to life is a sacred process of reweaving together lineages that have been broken and disconnected to revive a sense of shared humanity. In Buzzard Dances & Pokeberry Spells: Feathers, Folkore & Fugitive Fire I explore how bird folklore from both the African continent and the African American diaspora offers those who escaped enslavement a quiet source of resistance, a sense of collective identity, and a spiritual framework for survival in the face of dehumanizing power.

For communities shaped by a legacy of erasure and oppression, resistance to change often becomes a form of survival—so much so that even change made with care may be met with understandable caution. Yet, examples like Disney’s recent reimagining of The Little Mermaid featuring a Black heroine; Angela Carter’s bold retellings of classic folktales in The Bloody Chamber and Burning Your Boats, where she subverts old tropes to reclaim feminine power; and Somani Chainani’s Beasts and Beauty: Dangerous Tales, which revises timeless fairy tales through a queer lense as well as more feminist and racially diverse perspectives, remind us that reinvention can be a powerful act of justice. These transformations breathe new life into ancient stories, allowing them to evolve alongside shifting understandings of power, identity, and voice.

To end, I would like to offer an earth-inspired model and metaphor to imagine how an original story and its newer versions might relate to each other in a healthy reciprocal and interdependent way. It is drawn from the quiet wisdom of the natural world—one that lives in the seasonal relationship between Arctic Terns and Cloudberry Flowers. Each spring, I witness these small migratory birds pause to nest along the New England coast on their 22,000-mile journey from Canada to the southern tip of Africa. Though their stay is brief, they give something essential to the land: they carry and scatter the seeds of the cloudberry flower, allowing it to take root and bloom anew. And in return, the berries sustain the terns—feeding the very wings that will carry the seeds farther still. This is not a story of taking, but of mutual becoming. The tern and the flower are not fixed in one form or place, yet their bond is enduring—held together by movement, rhythm, and reciprocity.

What if we thought of storytelling in this way?

The original tale is the cloudberry flower and seed—rooted in ancient memory and quiet nourishment. But it is the flight of the new teller—the migratory tern, ever-between worlds—that carries it forward, scattering it into new soil and helping it bloom in unexpected places. Each version of the story feeds the next. And when the telling is told with care, the relationship between old and new becomes not a threat, but a generative dance—a love story. We honor the original not by keeping it earthbound, pinned to the past, but by letting it take wing on new winds and living breath. Change, then, is does not have to be erasure—it can be continuation. The past offers its fruit—sweet, wild, enduring—and the present, its dreaming wings. From their sacred exchange, something timeless is born.

To me, this is the essence of the Divine Feminine—a creative, regenerative force that welcomes many births and rebirths of the same soul-thread. It is movement, rhythm, renewal—just as Puss in Boots, that ever-evolving trickster with a flair for reinvention, continues to seduce and surprise us across centuries and screens. A tale retold, a pawprint left in new soil—and the tango goes on.

From petal to plume, from voice to vine—

Old stories soar through sacred design

Old fruit feeds the new one’s flame,

In love’s long dance, the story remains. . .