From shipwrecked hearts to shorebound farewells, many ancient oceanic legends are shaped by stories of love and loss, mourning and memory. It is not incidental that these stories of grief take place along the ocean’s edge. One could feel, even faintly that, in these myths and legends the ocean is a character in Her own right, a presence that deepens the story’s emotional tide, not merely a backdrop to its unfolding drama. As a great mother bearing witness to a tragic story, her saltwater depths cradle and honor the salty tears shed. Like the ritual of using salt as a healing salve, the sea itself becomes a balm ritualizing grief and softening it into something the heart can hold. Whether it is the heartache of the Celtic Selkie who is forced to leave her child behind to reclaim her stolen pelt, or the grief of the Inuit Sedna who is betrayed and cast into the sea by her own father and becomes the great Mother of the Sea, or Yemaya of the Yoruba tradition who holds both fertility and sorrow within her waves and so many more, the ocean intensifies the story’s emotional resonance, becoming a force that holds and transforms what is too heavy to bear. . .for those who live the tale and for those who bear witness to it.

Etymologically, there are words we use in both French and English that reveal intriguing echoes of this entanglement: mer (sea), from the Latin mare, and mort (death), from mors/mortis, coexist in French as linguistic siblings whose roots gesture toward a profound symbolic relationship. To this trinity, we might add mère — the French word for mother — whose phonetic closeness to mer suggests a deeper kinship, as if language itself remembers that the sea, too, is a mother. In English, marine stems from mare (sea), while mortal, mortality, and morgue arise from mors (death). Though distinct in origin, these words intermingle in cultural memory, where the sea is imagined not only as mourner and place of return, but also as a deep, nurturing mother — a womb of endless transformation. In this way, it makes sense that mer, mère, and mort — alongside marine and mortal — drift together like tide and undertow, carrying traces of origin and ending, of grief and becoming. This linguistic closeness mirrors the thematic intimacy found in myth, where the ocean is both grave and cradle, shaping emotion as much as it shapes narrative. This echo hums through legend and lore, where the sea, often resembling a wild mother, cradles sorrow in her salty womb — birthing from grief new stories that soften the heart, turning loss into a tide of renewal along the shifting shorelines where worlds dissolve and are reborn.

One of the oldest recorded myths is the Babylonian Epic Enuma Elish dating back to the 18th century BCE, which centers around Tiamat, a saltwater goddess depicted as a dragon or serpent. Tiamat represents the primordial saltwater and is one half of the original cosmic pair along with Apsu, the freshwater god. From their union, the first gods are born. Eventually, Tiamat is betrayed and killed by the storm god Marduk, and Tiamat’s fragmented body births the world, embodying the ocean’s fierce duality as source of both creation and sorrow, where every ending holds the promise of new beginnings. Tiamat is not simply in the sea—she is the sea—making the ocean itself the origin of creation and the crucible of transformation. The tale’s concept of the ocean as a womb that births the world becomes all the more impactful because amniotic fluid, the fluid surrounding a developing fetus, is similar to seawater in its salt content. Both fluids contain similar proportions of salts, reflecting the fact that life originated in the ocean, which is why the ocean lends itself well to the concept of being a nurturing mother, and a womb-like environment that births new life. Here again, the mythic sea acts—not passively, but as initiator, mother, and mourner.

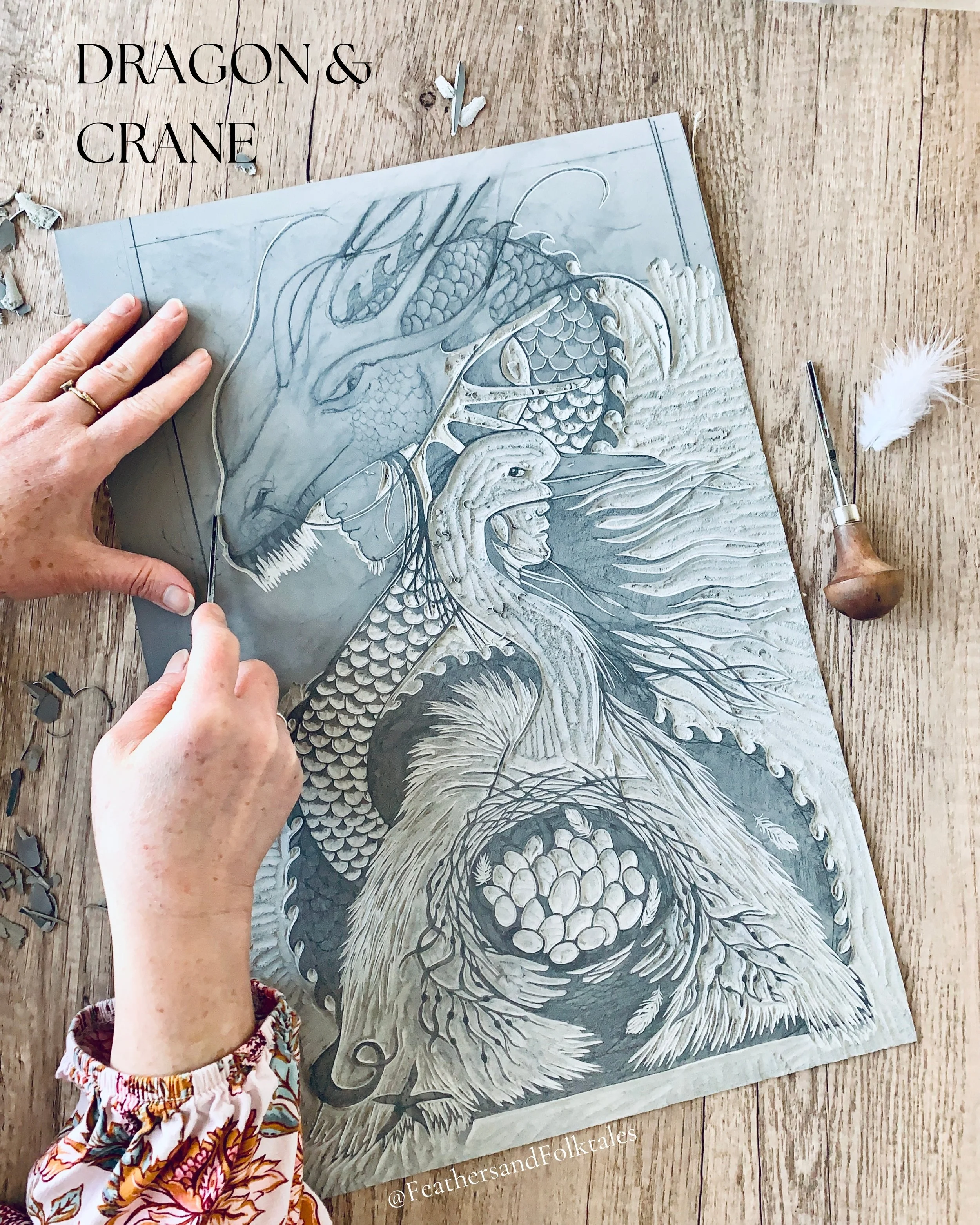

In the process of hand carving a linocut inspired by the Vietnamese maritime myth of Lạc Long Quân and Âu Cơ, Dragon and Crane.

From the coastal wetlands of Vietnam comes another myth of creation that entwines ocean and birth, love and loss. It tells of a love story between Lạc Long Quân, the dragon of the sea, and Âu Cơ, the mountain fairy or crane — a sacred union of scale and feather, ocean and land, that births the Vietnamese people, but ends in their parting, echoing the ancient rhythm where connection, grief, and creation flow together like tide and memory. This tale captures how grief and love are entwined forces, and the story is shaped by and felt most deeply through its oceanic salty bittersweet background setting, where every tide carries the memory of parting and return. In stories like this, the ocean is not simply stage-setting, but a presence that deepens the story’s emotional tide.

Together, the story of Tiamat and the love story of Lạc Long Quân and Âu Cơ, reveal how the ocean is not a passive background landscape but shapes the story’s soul and enduring resonance. It’s as if the myths chose their wild, watery homes knowing the ocean’s pull would carry the depths of their grief, their untamed power, and creative potential. Without the ocean’s presence, these stories would lose their emotional impact and transformative power—their capacity to hold grief that otherwise has no place to go.

The sea has always had a way of drawing out pain and turning it into something bearable. Across cultures and centuries, sea salt was more than seasoning - it was medicine: Egyptians, Greeks, and Romans soaked wounds in saline baths or applied salt-and-honey salves to disinfect and calm inflammation, while Roman soldiers used seawater directly to cleanse battlefield injuries. In Mesoamerica, the Aztecs combined salt with agave sap to reduce inflammation and speed wound healing, and in China, salt was a key ingredient in the Compendium of Materia Medica as an antiseptic and tonic. Salt’s ability to draw out infection—even when painful—mirrors the ocean’s paradox: it stings like grief yet purifies and heals at the same time. Many ancient medicinal practices prescribe coastline retreat as a healing ritual. In European Victorian and Georgian eras, doctors encouraged patients—especially those with respiratory ailments like tuberculosis and asthma—to spend extended periods by the sea, trusting that salty sea air, sunshine, and seawater bathing would revitalize the body and calm the spirits. This belief led to the rise of seaside sanatoria and sea-bathing regimens, where patients inhaled iodine-rich aerosols and let the wind off the waves carry away their troubles. Like the ocean itself, myths position the sea not simply as setting, but in story the ocean becomes a living salty metaphorical salve. It is the ocean’s wild, embodied presence that enables the myth to do its work—it becomes the medicine, not just the scenery.

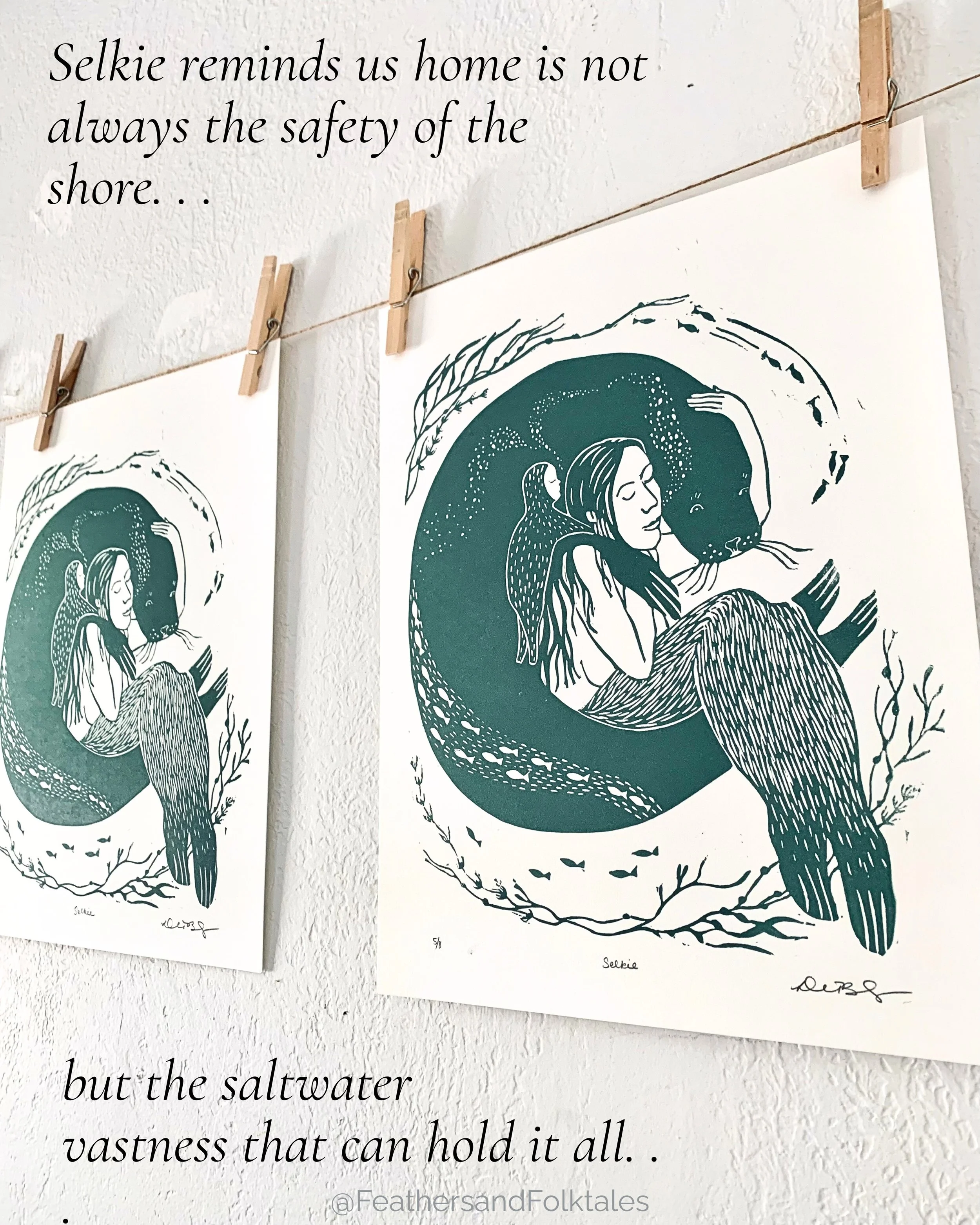

Along the ragged coastlines of Ireland, Scotland and Iceland, the story of the Selkie emerges — a haunting tale where love, loss, reclamation and grief are braided into the tides. A shapeshifting seal-woman is held captive on land after her lover steals her seal skin and makes her his wife. Although Selkie reclaims her stolen seal skin and returns to her home the sea, she also leaves behind the child born of her marriage with her captor. The bittersweet joy of finding her pelt, and grief of her departure, lingers not just in the story, but in the reader — unresolved, aching. And it is the ocean that holds in its depths and wide embrace what the characters cannot carry: the mother’s sorrow, the child’s abandonment, the ache of things left hanging unanswered and unreconciled. In this myth, as in many others, the sea is not a mere setting but a living presence — a wild, maternal force that cradles pain too deep for land-bound hearts and resolves the tension of what is left unhealed. The sea here becomes both refuge and reckoning, the only place capable of metabolizing the emotional weight of the tale. Here, the ocean becomes a sacred witness, a keeper of grief and rebirth, holding space for what cannot be reconciled.

In stories like these, the ocean becomes a co-creator in their retelling. Her presence is not passive—it rises up, shaping each version anew with tide and breath. Each time the story is told, it is shaped by the Her presence and power. Anthropologist Mary Douglas reflects on how ritual and symbols help cultures make sense of disorder, ambiguity and the sacred. She suggests that ritual serves as a kind of cultural memory—a structured, symbolic practice that helps people collectively process and internalize complex experiences like grief, transition, and transformation. When a sorrowful tale unfolds by the sea, the ocean herself becomes part of the ritual of its retelling. Her salt mirrors our tears and the healing salve of salt. Her depths echo our loss. Her timeless tides rising and falling mimic how grief can come in waves, and her ties to motherhood and her seemingly infinite expanse suggests arms big enough to embrace it all. All these layers interconnect and gather in the story and echo through its telling. In this way, a maritime myth becomes a kind of living altar. The ocean’s presence doesn’t just hold the story—it sanctifies it. She becomes the rhythm, the container, the salve that allows sorrow to soften, grief to be honored, to transform, and be carried home.

Across cultures and centuries, salt has done more than season and heal. Long before refrigeration, salt was a quiet alchemist: curing fish along the banks of the Nile, fermenting vegetables in Neolithic clay pots, drawing sweetness and longevity from what would otherwise spoil. In Mesopotamia, China, Europe, and across Indigenous traditions, salt-enabled fermentation didn’t merely prevent decay—it invited transformation. Through the slow work of time and microbes, raw perishables were turned into deeper nourishment: richer in flavor, gentler on the body, more wholly digested. So too with myth, especially those steeped in ocean and salt. Saline stories—sourced from brine-soaked shores—carry the weight of sorrow not by eliminating grief, but by transforming it. Like food left to ferment, these tales allow pain to break open and breathe, to soften and swell into something that can be held, even swallowed. This transformation is not metaphorical alone—it is made possible by the sea’s own elemental processes, which myth mirrors. The salt of the sea, both literal and symbolic, acts as a preservative of memory, but also as a fermenting agent—making the bitter more bearable, the raw more resonant. In this way, oceanic myth becomes emotional sustenance: a means through which sorrow is not only preserved, but made nourishing—digestible in its depth, and enduring in its meaning.

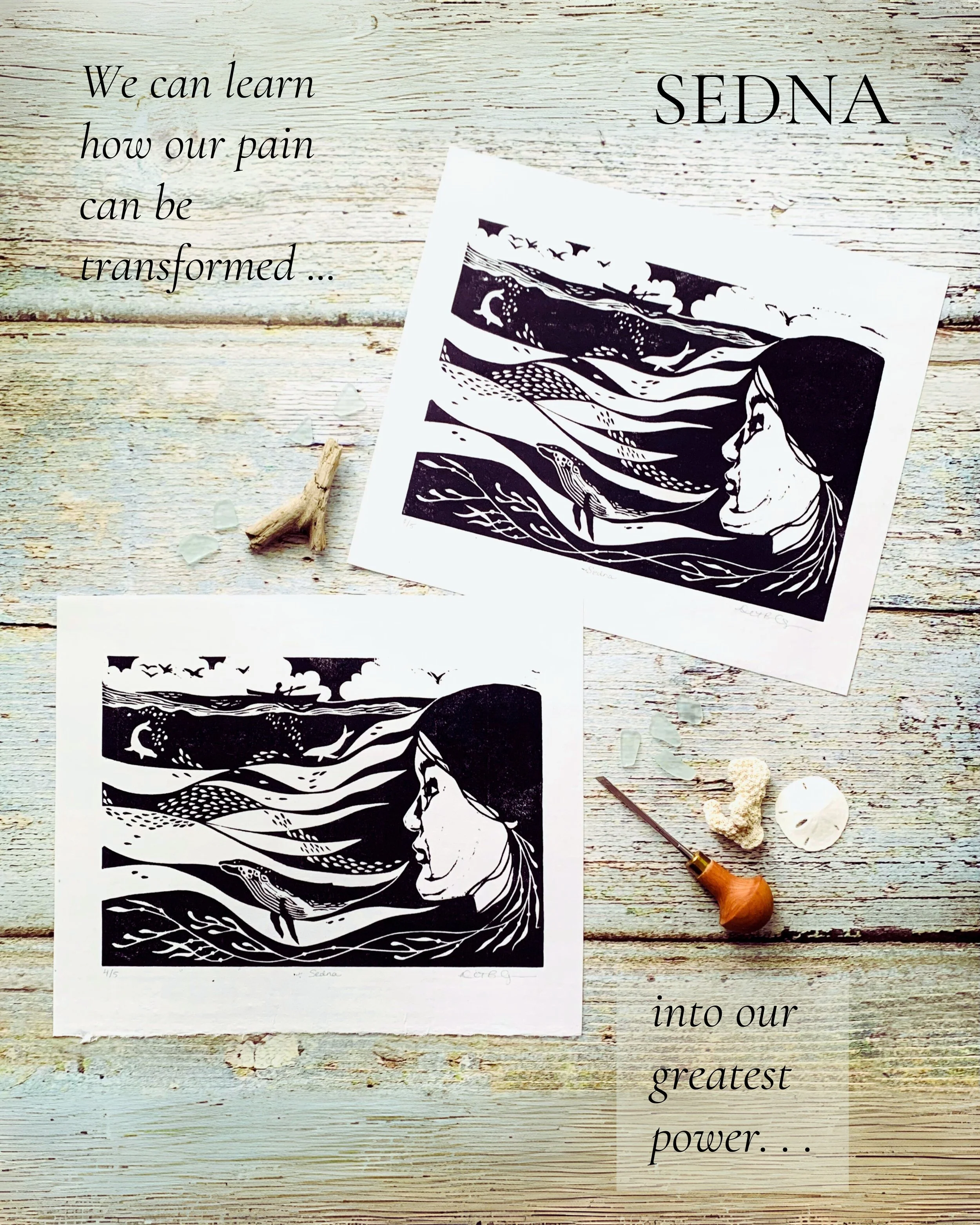

In the Inuit myth of Sedna, the heroine is betrayed by her father and lover and cast beneath the surface, only to rise as the sea’s powerful mother. Her descent and transformation speak to how the ocean serves as the saltwater underworld brine in which the heroine heals from her wounds and emerges transformed. Her descent and transformation speak to the depths of betrayal and rebirth, embodying the ocean’s capacity to hold the darkest grief and transmute it into fierce creation and renewal—reminding us that from suffering, new life and strength can emerge. Again, the sea is not simply where the story happens—it is who makes the transformation possible.

Finally, the ocean holds primal significance as the wellspring of all life—science now confirms that our most distant ancestors emerged from its depths billions of years ago. This ancient sea, the cradle of existence itself, is not merely a backdrop for stories of loss but the very birthplace of life’s unfolding journey. To grieve by the ocean, then, is to touch a memory older than humanity—a deep mourning intertwined with the collective origin of our being. In this light, the ocean becomes a sacred space where loss resonates with creation, and where the ebb and flow of sorrow mirrors the rhythms that have shaped life from its very beginnings. The sea’s ancient memory becomes part of the mythic transmission itself.

Across Yoruba and Afro‑Caribbean traditions, Yemoja (also known as Yemaya or Lemanjá) reigns as the ocean’s mother, a creation goddess who bridges sorrow and renewal. Yemoja’s name itself—“Mother whose children are the fish”—echoes her role as marine mother, and she cradles fishermen, mothers, survivors, and lost souls alike, her brine both preserving and transforming their sorrow into something bearable, even nourishing. According to a Yoruba creation myth, Yemoja descended from the divine realm alongside the orisha Obatálá, assisting in the shaping of humanity—her waters breaking in a deluge that forged rivers, streams, and the first mortal forms. In another account, grief drove her tears across barren land, birthing life-giving rivers with the fluidity of mourning—making her sorrow the source of beginnings. This is where the metaphor deepens. Just as salt preserves and provokes fermentation, allowing raw, perishable foods to evolve into richer, digestible nourishment, so too does this saltwater myth ferment grief into meaning. In salty oceanic space—an arena both maternal and mercurial—pain is not erased but tendered, softened into a wisdom we can swallow. Yemoja is the ocean—feeling, shaping, transforming the story itself.

It is in the saltwater womb of the ocean that folktales of grief and loss find their voice. The sea is not just a landscape outside us where these myths unfold—it’s the saltiness of her waves that echo our own tears, her cavernous depths that mirror the felt loss, her crashing waves that echo the heart’s rupture, and the tidal rhythms that echo the grief —visceral, remembered, and made manifest. She holds what is too heavy for us to carry alone. Salt, in its many forms, becomes a conduit: a healing salve, a sacred preservative, the fluid of birth, the sting of loss. These layers allow myths to approach grief with tenderness, to ferment sorrow into meaning—making what might otherwise be unbearable, endurable. In tales of Selkies, Sedna, Tiamat, Yemoja, and Âu Cơ, we enter a mythic tide where pain is not resolved, but ritualized—where loss is not overcome, but honored. The ocean is not background, but a breathing, mythic mother—storyteller and sorceress, carrying the impossible into form. In turning to the wild—waves, salt, and ocean—we find not escape, but a language through which our deepest human experiences become bearable, meaningful, and beautifully told.

References

Cirillo, M., Capasso, G., Di Leo, V. A., & De Santo, N. G. (1994). “A history of salt”. American Journal of Nephrology, 14, 426–431.

Denton, D. (1982). The hunger for salt: An anthropological, physiological and medical analysis. Berlin: Springer‑Verlag.

Douglas, M. (1966). Purity and danger: An analysis of concepts of pollution and taboo. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul

Porter, R. (Ed.). (1990). The medical history of waters and spas. London: Wellcome Institute for the History of Medicine.

Ritz, E. (1996). The history of salt – aspects of interest to the nephrologist. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation, 11, 969–975.

SelectSalt.com. Preserving food with salt: A time‑honoured tradition.