A giant statue of Quan Yin (known in Vietnamese as Quan Thế Âm, Avalokiteshvara Bodhisattva) at Linh A Pagoda in Đà Lạt, Vietnam. Photo credit: Vika Glitter on Pexels

What if the voice of the Sacred Feminine has always whispered through the grain of carved wood and the press of ink to paper—Her breath present in the very act of carving and printing? In this passage, I trace how the the rustle of Her knowing resounds in the words of one of the earliest block-printed texts—the Heart Sutra—and also in the ritual of printmaking itself, so voice and vessel, language and labor, text and craft are not separate, but part of the same living thread. I follow the echo of the Heart Sutra’s ancient wisdom—that form is emptiness, and emptiness is form—as it lives on in the printmaker’s hands: carving away to reveal, subtracting to create. Both are threads in a lineage that remembers the sacred call to reweave back into the tapestry what has unraveled at the seams.

Within the unfolding mystery of printmaking’s lineage, one of the oldest and most prolifically blockprinted texts is the Heart Sutra* which carries the Buddha’s wisdom as passed to his disciples through the resounding voice of Avalokiteśvara—later known in China and East Asia as Quan Yin, or the Goddess of Compassion. Through the rhythmic pulse of sacred poetry The Heart Sutra’s main message is about the reweaving of opposites, what is also well known as non-duality, Oneness, or Sacred Union. It guides us to loosen our grip on rigid beliefs and fixed identities turning our attention to threshold between worlds, where opposites touch and tangle. According to the late Zen monk Thích Nhất Hạnh in his book The Other Shore: A New Translation of the Heart Sutra With Commentaries, the Heart Sutra reveals how all things “inter‑are,” without fixed boundaries or separate selves but in a spacious and dynamic field of interbeing and interwoven, where nothing exists in isolation. He explains that the Heart Sutra shows us how Birth and Death meet at the same source, and how Self and Other have roots that drink at the same well. welcoming us back to the sacred threshold loom where scattered worlds are stitched into kin.

The wisdom of the Heart Sutra is woven even into the name “Sutra” whose very etymology comes from from the sanskrit word sūtra, a thread, suggesting a weaving together of things, and also from sukta, a “wise saying” pointing toward the idea that this weaving is itself a form of wisdom. This ancient thread winds its way into English too, through the word suture, meaning to stitch or bind. Though they arose in different languages, both words descend from the same root—an old Indo-European verb meaning “to sew.” One mends flesh, the other meaning. Both are acts of sacred repair.

This ancient and sacred paradox—the union of opposites—comes alive through the printmaker’s hands. As a linocut printmaker working mostly in single colors, I find myself continually tending to the balance between what is carved away and what remains and their interdependence, where absence births presence, and what is taken becomes what is given. The craft itself becomes a dance of dualities: wood and ink, pressure and release, absence and impression. It is a creative ritual enactment that hums the Heart Sutra’s voice and vision: that opposites are not rivals, but lovers entwined, each calling the other into being.

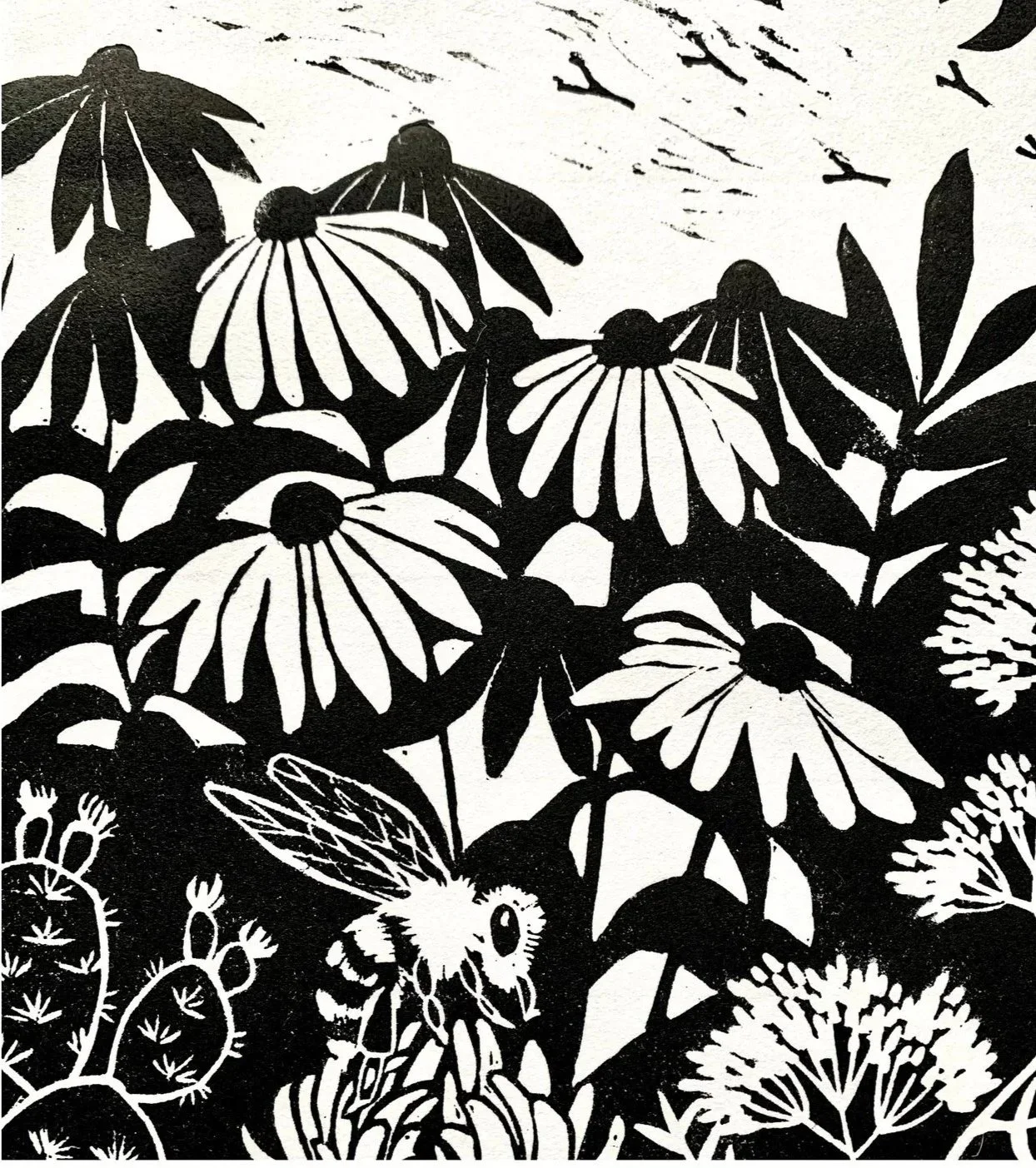

You can see this play out in the close-up photograph of the echinacea flowers below/right, where the dance between positive and negative space comes alive. Some blooms are defined by what is carved away—the negative space—while others emerge from the solid areas of ink, the positive space. To make the lighter flowers stand out clearly, I had to carefully arrange the darker silhouettes around them; otherwise, they would have blended into the background sky, which is also carved as negative space. I must use the dark to reveal the light, and the light to shape the dark—each bringing the other into being. This echoes the essence of non-duality, where darkness and light are not rivals but born of each other, each incomplete alone, but together creating a unified whole.

In the close-up photograph of Sky Woman’s profile below/right, we can see another interdependent relationship between opposites at play. Carved within her head is the shape of a bird, formed from negative space—a delicate silhouette that holds within it a cluster of leaves, some shaded dark, others light. Nestled inside a few of these leaves are drifting dandelion seeds. The way the face, the bird, the leaves, and the seeds are integrated together echoes Thích Nhất Hạnh’s teaching of interbeing—each element existing not alone, but in harmonious union, breathing life into one another.

In the larger SkyWoman design as a whole (see right/below), the bird’s white wing shapes the daylight sky, with dark birds flying within it. This entire scene is set inside Sky Woman’s dark profile and hair, which form the night sky, where white birds and a crescent moon stand out in contrast. Calling each element into harmonious relation within the frame is the block printer’s devotional task echoing the very message the Heart Sutra delivers: that form and emptiness are not separate, but interwoven each arising from the other to weave a unified tapestry of belonging. Here in the printmaker’s studio text and craft, voice and vessel, language and labor are woven from the same sacred lineage, where shadow and light are cradled and woven into one. In this way, the printmaking design process becomes more than a craft—it becomes a quiet, contemplative practice.

The subject of this print is inspired by a Haudenosaunee creation myth of how two separate worlds become entwined: Sky Woman falls from the sky, carrying seeds, nuts, roots, and saplings from her celestial home, and with the help of the earth’s creatures who rise to catch her fall, she gives birth to a new world born of both sky and earth. Both print and story, labor and lore embody The Great Weaving and Sacred Union in the resounding voice of the Heart Sutra’s universal wisdom of Oneness.

This sacred interweaving lives not only in the words of the Heart Sutra, but in the one who speaks it. Legend has it that Quan Yin was a being who witnessed the enormity of suffering in the world and became so overwhelmed and overcome with grief that her body shattered into a thousand pieces. The Buddha witnessed this rupture and gathered Quan Yin'’s scattered body, tenderly piecing back together a new being with many heads, arms, eyes and ears—so that every distress would be seen and every need heard and attended to. This mythic rebirth reminds us that within the divisiveness and polarities we witness both out the world and within us we, too, can become whole - that our separation is not the whole story.

The variety of forms of the Goddess Quan Yin. Photos are courtesy of Canva.

Although Quan Yin is known as a female bodhisattva in East and Southeast Asia, s/he was originally depicted as male in India where s/he was named Avalokiteśvara. The multiplicity of her gender identities** also mirrors the very teachings she carried—blurring boundaries, transcending binaries, and reminding us that compassion is not the erasure of self or other, but a sacred union and sense of shared interwoven belonging.

We can witness the depth of devotion the Heart Sutra inspired through the many block prints—as well as sacred relics, talismans, and protective amulets—that history has left behind. Its poetic rhythm made it easy to chant, memorize, and pass from mouth to ear, heart to heart. And perhaps it’s no surprise that its core teaching—that opposites are not enemies but lovers, dancing one another into being—echoes across many other spiritual lineages. In the Hindu Shiva and Shakti we find two divine forces not opposing, but completing one another, revealing that all creation arises from their sacred oneness. The Goddess Kali, also from Hindu mythology, is both fierce and holy, destroying not out of hatred but of love, severing illusion to make way for truth. The Black Madonna embodies non-duality by holding both suffering and radiance in a single embrace—her darkness not the absence of light, but its fertile source, where grief and grace, shadow and sanctity are woven into one sacred whole. Spider Grandmother, from the Hopi Indigenous North American tradition, spins a web connecting all beings where creation and destruction, past and future, matter and spirit are not separate threads but part of one continuous, sacred design. And Isis of ancient Egyptian mythology, in the silence of her grief and the strength of her magic, gathers the broken body of her beloved and makes it whole again. These goddesses, in the same spirit as the voice of the Heart Sutra itself, remind us that the separation we perceive between spiritual traditions is not the whole story—only a version cast partly in shadow. Though their lineages span different cultures and continents, their mythic roots are nourished by the same sacred soil, drawn from the same shared well of wild earthly wisdom.

The Black Madonna (left) and Quan Yin (right). Quan Yin is often depicted with a small baby in her arms representing her role as the goddess who grants children or as a symbol of compassion and nurturing. This version is sometimes called the "Child-Sending Guanyin" or “Bestower of sons”. Photos are courtesy of Canva.

In the process of hand-carving and printing designs inspired by ancient folktales from distant geographies, I witness echoes of the Heart Sutra in the folktales themselves. From the shapeshifting Fox Woman who appears in Japanese, Chinese, Irish, Finnish, and Inuit stories, to the ancient trio of hares, the divine feminine, and the moon that appear in four continents, and the Raven Goddess from Celtic, Slavic, and Hindu traditions—these tales, though scattered by distance, culture, or time and hold synchronicities that suggest a shared sisterhood waiting patiently to be rediscovered, hand carved, printed and honored once more. Perhaps the folktale that echoes the Heart Sutra most vividly for me is the Weaver of the World, who sits reweaving back together the stray threads from her fabric that Raven continues to peck apart. She, like Quan Yin, like the resounding voice in the Heart Sutra, draws our attention to the threshold loom where the threads of far-flung worlds entwine once more.

What began as an ancient devotional act of carving wisdom into wood has retained its mystique into modernity, printed and passed from hand to hand through the steady rhythm of generations - a lineage which I feel honored to take part in as I sit in my studio carving. Printmaking to me is a quiet, embodied prayer—a contemplative practice that honors the deep interwovenness of all things. Echoing the Heart Sutra, the craft is a living sutra that turns our attention to the seam where scattered worlds are stitched into kin. The question remains: in a world often divided by boundaries and binaries, can we learn from this ancient art and its sacred teachings to hold the light and dark, the seen and unseen, in a single breath? What might we become if we truly remembered that we are not separate threads, but part of the same eternal weave? These are the questions that whisper from the labor, the making, and the craft. . . Calling us back to the mythic loom where matter and mystery are eternally being woven into one.

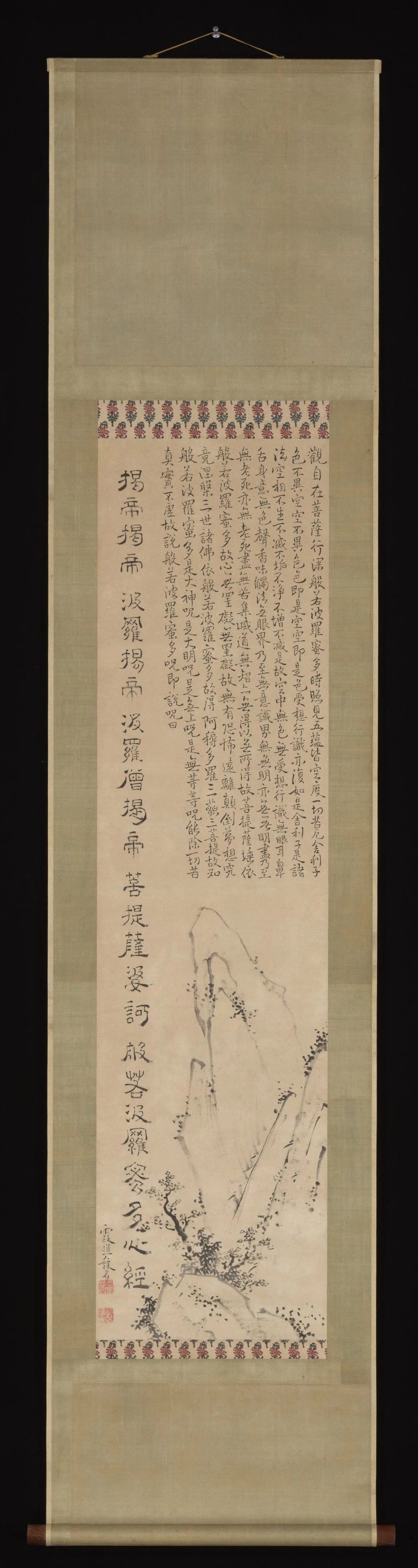

Heart Sutra (Hannya Shingyō) and Landscape by Japanese artist Ike no Taiga from the Edo period (1615-1868). This short but profound Buddhist scripture distills the core teachings of the Diamond Sutra—the oldest printed text—into a poetic form. This is a public domain image available on MetMuseum.org

Notes:

*Avalokiteśvara’s transformation into the female form of Quan Yin in China reflects how Buddhist teachings were syncretized with Daoist traditions that honored feminine spirituality. In other Southeast Asian cultural landscapes - such as Vietnam where feminine-centered cosmologies, matrilineal values and mother goddess worship were part of the indigenous value system—she was also embraced in her female form.

**I find it fascinating the Heart Sutra includes the word “Heart” in it. Heart Sutra is named not for the organ that beats in our chest — though that would be a fitting metaphor — but because it distills the very heart, the luminous core, of the Buddha’s teaching on emptiness. Even so, it’s hard not to notice the poetry of its name: a sutra that lives in the heart, speaks to the heart, and asks us to see with the heart. And perhaps it is no accident that in many spiritual traditions, including Buddhism, it is the heart — not the head — where the deepest wisdom is said to arise.

Long before the heart was reduced to a mechanical pump, it was revered across cultures as the original seat of knowing. In ancient Egypt, it was the heart—not the brain—that was weighed in the afterlife to judge the soul's truth. In Chinese medicine, it is the emperor of the body, the keeper of spirit. Mystics, both Sufi and Christian, have long listened for the voice of the Divine within its chambers. Even modern science now echoes what the old stories have always known: that the heart carries its own kind of intelligence—40,000 neurons pulsing with memory, perception, and choice. It speaks in a language older than words, in pulses and pauses, in the ache and opening that mark what matters most. To call it the “first brain” is not just metaphor, but a remembering—of a time when wisdom began in the chest, where the breath catches, where love lands, where the invisible becomes known.

Photo credit:

Taiga, Ike no. Heart Sutra (Hannya Shingyō) and Landscape. 18th century, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/75347. Accessed 15 Oct. 2025.

References:

Fuller, Angela. (24 October 2023). “Guanyin: Bodhisattva, Goddess and Queer Icon.” www.taftmuseum.org, [Retrieved October 15. 2025].

Thích Nhất Hạnh. The Other Shore: A New Translation of the Heart Sutra With Commentaries. Parallax Press, 2017.