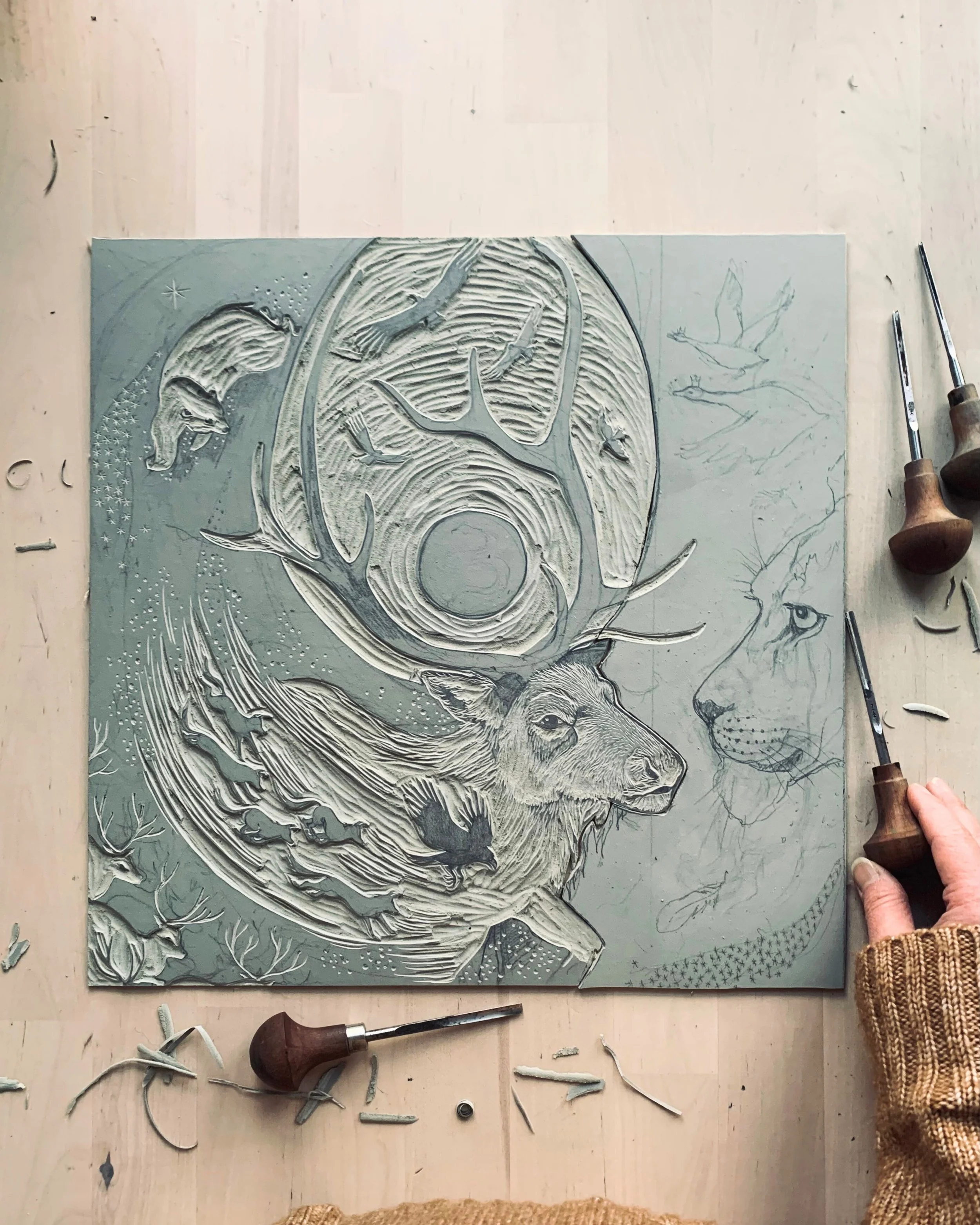

Beginning to carve a design inspired by creaturely beings who carry the sun from different ancient and living cultures

In the deep memory of our storied Earth, as the year turns, we can witness the sun returning and brightening, and finding its place once more among the rhythms of life. Prior to and alongside solar deities, in both ancient and living traditions, the sun’s fierce and untamed blaze is tempered and made knowable through the ordinary enchantments in the wild: the ageless hunt between predator and prey, the eternal cycle of hatching and birthing, the seasonal migration that returns. From the Arctic tundra, to the sun-scorched savannah, to the lake-woven forests of the far north, our furred and feathered creaturely kin carry the sun across the sky, free it from captivity so we may benefit, and tenderly watch over it like a devoted mother until it hatches the dawn. In the spell of the telling, the sun we so deeply depend upon is no longer distant or ungraspable, but held with care—protected, carried and nurtured by creature kin who draw her more intimately into belonging with the earthly realm. The world begins to feel a little safer, the sun’s intensifying light a little less indifferent, and instead something we can surrender to, dwell within, and trust the magic of its unfolding to touch us.

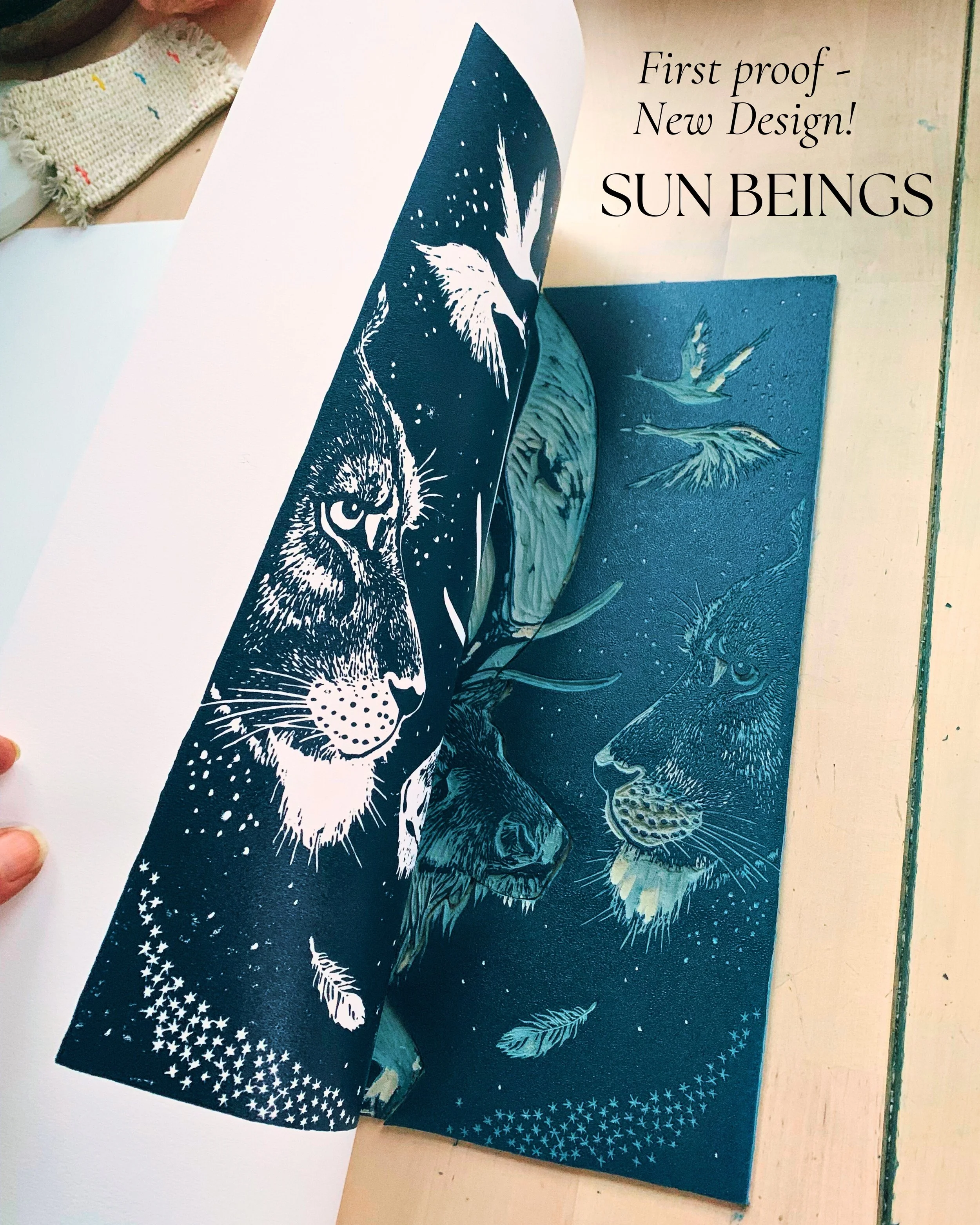

Pulling the first print!

Among the Indigenous Sámi traditions of Norway, Sweden, Finland and the Kola Peninsula, as the sun wanes and winter approaches she moves in rhythm with migration, cradled between the antlers of her reindeer mother Beavi, and as the year unfolds, she trudges alongside mother Bear like one of her cubs. Here, the sun does not blaze as a distant, indifferent stranger, but is ushered in creaturely timing, belonging intimately to the herd. In Sámi language eallu is the word that means herd, but unlike English, where herding places humans in command, eallu also carries the sense of surrendering to the animals. Etymologically, it also means kin and links to eallin, life itself. As the herd cradles the sun, the brightening light feels woven into a familiar earthly rhythm. Our vigilance softens and our defenses ease because the sun is under the protection of the herd, allowing us to soften, surrender and meet life with a little more trust, presence, and a quiet sense of enchantment.

Woodblock print depiction of the legendary Emperor Jinmu tennô with the crow Yatagarasu surrounded by the sun by artist Tsukioka Yoshitoshi 月岡芳年 (1880). Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Yatagarasu, the three-legged Crow, dark-winged, clawed, and eyes alive with watchful knowing, serves as a solar messenger to the Sun Goddess Amaterasu Ōmikami, guiding the world in Japan’s ancient and living Shinto cosmology. The name Yatagarasu translates to “eight span crow” - a poetic way of evoking Crow’s immense, extraordinary size and presence who - coupled with the Sun Goddess - embodies light, cosmic order, divine guidance. Through the black wings of this feathered familiar, the distant divine sun is brought into relationship with the world of creatures and humans alike. Distant power is rendered accessible, cosmic order made tangible, reminding us that the Sun’s light is something we can interact with in the earthly realm and meet as kin rather than stranger. It was Yatagarasu who lead Japan’s first Emperor on his journey eastward towards the imperial capital founding Japan’s imperial line, reassuring us that the Sun’s luminous, life-giving presence was watching over him through Yatagarasu’s careful guiding which ensured this revered ancestor his good fortune. In this story of Yatagarasu we are brought to a deeper remembering that we live in a sentient universe where every being moves with purpose, every creaturely movement is a dialogue with the divine. You can find Yatagarasu by the name of Sanzuwu in China and Samjok-o in Korea where he appears in ancient murals, a dark-winged sentinel amidst a blazing sun, symbolizing cosmic order and the unity of all forces. Yatagarasu’s three legs suggest a kind of mythic stability and completeness beyond the tension of duality - the generative third where Heaven, Earth, and Humanity converge, when polarity becomes movement. In union with the Sun Goddess, crow and light together enact a life-sustaining rhythm through which cosmic order is continually born.

Raven, the powerful trickster, from the traditions of the Pacific Northwest (known as Yéil for the Tlingit, Yahgul for the Haida, Txamsem for the Tsimshian, and Xwe’lát’ for the Coast Salish) acts on our behalf, stealing the Sun back from her thief, a great chief who hides the sun in a cedar box. Transforming himself into a hemlock needle, he drifts into the drinking water of the chief’s daughter who unknowingly swallows it, becomes pregnant and births Raven in human form. Raven boy grows up wise and cunning, claims innocently that he is curious about what’s in the box until his grandfather relinquishes it. Raven boy seizes this moment to transform back into his bird form to grasp the Sun in his beak, and flies through the smoke hole and releases the Sun into the sky for all to benefit. His black feathers are scorched by the smoke in this flight - the cost of bringing light to the world. Here, it is the courage and selflessness of a black-winged bird who dares to intervene on our behalf—who brings balance to the chaos around us. In standing up for us, risking himself, and bearing the marks of his effort, he signals to the soul: you are seen, you are held, and the world though wild, is safe. Under his protection, a quiet trust begins to unfold within us; the sun will rise again, the rhythms of life persist, and we may open ourselves to reflection, connection, and the comfort of knowing a feathered trickster friend keeps watch nearby.

Within the spell of these three stories of Reindeer Beavi, Crow Yatagarasu, and Raven Yéil, the sun shifts from its distant indifferent place to a more intimate presence woven into the rhythms of the creaturely and earthly world we inhabit. When the sun is stolen and raven returns it, when crow guides us with the sun’s divine spirit, or migratory reindeer cradle her across the sky, change is not imposed from above but co-authored by earthly creatures. Though we deeply rely on and need this radiant mother for our human survival, and the threat of her indifference stirs the old, trembling fear of our inner child left alone, with each creature who ensures her return we feel her golden warmth settling over us like a lullaby and we experience a gentle recalibration of our own sense of safety return. We can relax knowing we are protected from her absence, she is defended and nurtured for us, we are guided by her, and through this we find ourselves living within a world woven with care, alive with creature kin who watch over and sustain us. From this protected place we can move in alignment with our purpose, live with authenticity and presence, and meet the world with more appreciation, and perhaps even a sense of awe.

The sun - though nurtured by faithful creaturely kin - is never without danger however. Beyond these gentle guardians, solar predators remind us that creation and destruction are braided together in the rhythms of life. In Norse mythology it is Wolf, Sköll, who chases the sun goddess, Sól (or Sunna) as she rides across the sky in her chariot drawn by horses, bringing light and warmth to the world. Offspring of Fenrir, the colossal monstrous Great Wolf, and Angrboða, an earthly fertile feminine being, Sköll carries forward the dual legacy of his parents’ power—both creative and destructive. This primal, paw-thundering chase explains the daily and nightly movement of the sun across the sky, but his pursuit is never completed, revealing an ongoing tension between order and chaos, light and shadow, life and death. Though the shadowed Wolf Sköll is fang-bearing and bristled, and the aim of the chase is grave, the heart prefers the known danger over the nameless void, because predictability—even in peril—feels safer than the chaos of the unknown. The Sun and her canine pursuer are bound within a rhythm older than memory itself, where threat and preservation move together in a necessary balance. Anchored by the story of the primordial hunt, our grip on fear and the outcome loosens, and what we witness feels woven into a living whole to which we belong. From this place we are better able to see the world with trust, wonder, and a quiet sense of wholeness..

There is a second solar predator whose unbridled appetite and instinctive might echoes Wolf Sköll turning our experience of the sun once more into a story of the hunt, making sense of the Sun’s scorching heat as part of the timeless earthly rhythm of predator and prey. Sekhmet, “She Who Is Powerful,” from Ancient Egypt, is the Sun’s fierce heat made flesh: a she-lion of hunger, instinct, and untamed force. Like the Sun, she destroys and gives life by the same hand. Her blaze can scorch and kill, yet it also clears, ripens, and renews—just as the lion’s hunt feeds not only herself but the wider living world. Through Sekhmet, the Sun’s energy becomes regenerative: a power that burns away what cannot endure and restores vitality where life is ready to return. Egyptian physicians were called “priests of Sekhmet,” invoking her in healing rites, knowing that the same force that brings illness can also drive it out, purify the body, and return it to balance. By embodying the Sun as a predator, Sekhmet renders the sun’s vast, lethal power intelligible, its intense heat is translated into the familiar temperament of a she-lion in pursuit: her heat the closing of distance, her breath hot against the skin, her presence impossible to ignore. As she circles, patient and exacting, the sun’s scorching force becomes a presence and power we know how to meet, not because it is safe, but because it is alive, embodied, and governed by creaturely laws we recognize and accept.

In these two predator sun stories, the sun’s intensifying brightness is explained in the language of the timeless hunt - what we have always known how to live alongside, and answers to the same instincts that live in us. Through the creaturely perspective of predator and prey, these solar creature stories teach us to receive the world as it is, even its shadows and storms, as an integral aspect of the earthly realm. They recalibrate how we meet danger, restoring death and illness to the known fabric of life, so our grip on fear and outcome loosens and we can rest more fully in what is.

Photo Credit: Statues of Sakhmet in the Tokyo National Museum, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Finally, we meet the sun’s more liminal creaturely companions: feathered beings who birth the new and carry the dying and the dead, showing us how endings feed beginnings, and how the sun’s light is born again through their quiet labor. Condor, from ancient Andean traditions, is a revered living intermediary who connects the earthly and celestial worlds. Known as Kuntur in Quechua, Condor with his massive wingspan of more than three meters, carries prayers, messages, and blessings to the sky spirits and brings back sacred wisdom. Because Kuntur the Condor is often seen soaring near the sun, he is associated with the Inca sun deity Inti, who is considered an ancestor of the Inca people revered as the giver of warmth, light, and life—vital in the high Andes where sunlight drives agriculture, growth, and survival. Though Kuntur is a scavenger, in many Andean traditions this only deepens his place between worlds. Feeding on what has fallen, he carries life from decay back into continuity. In his slow circling and patient labor, Kuntur the Condor reminds us that nothing is wasted, that endings loosen into beginnings, and that life is always being woven onward. In witnessing this airborne, feathered, talon-clad mediator of the sun, we loosen our grip on our small mortal life, and awaken to the deeper remembering that all that dies is renewed, that the world is held, balanced, and whole. From this place we can meet the living universe - not with fear - but with trust, reverence, enchantment, and a renewed sense of belonging.

Born from the deep memory of an animate world, in Karelian and Finnish runic songs (which are part of the epic Kalevala tradition), a mythic water bird Sotka - resembling a snow goose, duck, loon or swan - lays an egg on primordial waters; when the egg hatches, its yolk becomes the sun, its white the moon, and its cracked shell a sprinkling of stars and planets including the earth. Here light is not deified or set apart or above us, but creaturely, earthly, born within the nest of a feathered bird who tenderly watches over the hatching of the dawn. Sotka embodies the principle that life arises from attentive care and relational presence, and in some traditions, she is thought to guide souls to and from the body, connecting human life cycles to cosmic rhythms. In this sense, she mediates between the human and the celestial, much as she mediates the sun’s emergence. Sotka symbolizes ongoing renewal: the rising sun each day can be seen as a re-hatching, a daily reactivation of cosmic order and her presence reminds us that endings are woven into beginnings. Through the story of Sotka, we are woven into sibling relationship with the sun, through our shared nest and the feathered embrace of our winged mother where we are held in the rhythm of birth, death, and becoming.

The Sun - an egg - surrounded by creaturely beings who carry, cradle, midwife the dawn. . .

Reflecting on these solar creatures and their stories, we are brought to a deeper remembering that we are living within a relational universe—awake, watchful, alive, and attuned. In tracing the sun’s path with its creatures, the poet Mary Oliver’s line, “You only have to let the soft animal of your body love what it loves“ whispers through my mind. As we are drawn into the story of the sun and her creatures, we “find our place in the family of things”, as she says, sensing how our instincts, longings, and fears echo the pulse of the living world. Like Sköll the Wolf, we can acknowledge our hunger and appetite; like Sotka, we can lean into our instinct to nurture and give birth; like Beavi the Reindeer, we can embrace the call to cradle a child; like Yéil the Raven, we can inhabit and honor our inner trickster that restores balance to the world. Living among our creaturely kin, we surrender to the wisdom of our instinctual nature—the primal, embodied knowing that Dr. Estés calls forth in Women Who Run With the Wolves—and move through the world’s birthing, hatching, dying, and renewing with reverent awareness of our small but vital verse in the world’s timeless pageant of living, breathing birds, beasts, and kin.

This precious wisdom, tenderly preserved for thousands of years in ancient stories of the sun, gifts us with precisely what we need for uncertain and chaotic times. Ilarion Merculieff, an Unangan (Aleut) Indigenous Elder from St Paul Island- also known as Kuuyux or “carrier of ancient knowledge and a messenger” - offers a similar message in the face of global catastrophe and changing times. He reminds us to watch the birds who “don’t worry about where they will find food tomorrow. They just are.” Like his ancestors before him—displaced by empire, yet carried by generations of unbroken spirit surviving in a harsh Arctic world —he speaks from an elder’s remembering: “This is the way my people lived: in fully embodied trust, without thought or fear. We lived our faith through our bodies, through the Earth, through the universe, and through the Great Spirit alive in all things. We must be peace. We must be love. And the rest will take care of itself.” If we trust in the ancient and timeless order of the creaturely realm, and loosen our grip on fear, a deeper remembering stirs: what falls is not lost, what dies feeds renewal, the world is always turning toward balance, ever whole. From this remembering, we open ourselves to life itself—not with dread, but with trust, reverence, and the quiet assurance that we, too, are creaturely, and belong deep in the heart of this earthly world.

References

Crawford, John Martin, translator. “The Kalevala: Birth of Wainamoinen.” TOTA.world, TOTA Curated Archives, www.tota.world/article/2551/. Accessed 16 Jan. 2026.

Dillon, Lauren. “Skoll and Hati: The Norse Wolves Who Chase the Sun and Moon.” Historic Mysteries, 24 Aug. 2023, www.historicmysteries.com/myths-legends/skoll-and-hati/35927/. Accessed 16 Jan. 2026.

Merculieff, Ilarion. “Living from the Heart.” In Jamail, Dahr, and Stan Rushworth, editors, We Are the Middle of Forever: Indigenous Voices From Turtle Island on the Changing Earth. The New Press, 2022, pp. 30—47.

Mishan, Ligaya. “In the Arctic, Reindeer Are Sustenance and a Sacred Presence.” The New York Times, 9 Nov. 2020, www.nytimes.com/2020/11/09/t-magazine/reindeer-arctic-food.html. Accessed 16 Jan. 2026.

“Raven (Mythological Figure).” Eyes of Azrael: Native American Mythology, Eyes of Azrael, www.eyesofazrael.com/mythos/native_american/spirits/raven.html. Accessed 16 Jan. 2026.

“Sacred Animals in Inca Mythology: The Inca Trilogy Explained.” Inka Time Tours, Inkatimetours.com, 25 Apr. 2025, www.inkatimetours.com/sacred-animals-in-inca-mythology/. Accessed 16 Jan. 2026.

Uth, Alexandra, MA. “Sekhmet (Deity).” Research Starters: Religion and Philosophy, EBSCO, 2022, www.ebsco.com/research-starters/religion-and-philosophy/sekhmet-deity. Accessed 16 Jan. 2026.

“Yatagarasu.” Yokai.com, Yokai.com, https://yokai.com/yatagarasu/. Accessed 16 Jan. 2026..

Where does the human heart go to be remade when our current lives cannot cradle us? In the world of folktales and fairy tales, pelts, furs, and feathered cloaks do so much more than adorn and protect —they cradle the heroine through moments of quiet transformation, guiding her from disempowerment to agency, from a borrowed life to one lived in truth. Whether it is Mossy Coat wrapped in living moss, Allerleirauh cloaked in many furs, or Kråksnäckan in raven feathers, these woodland garments become living sanctuaries. Within the safety of their folds, the soul unravels, heals, reassembles, nurtured by the living wild. Through Deep Time these tales whisper of a woodland wardrobe, always patiently waiting to cradle us anew.