This beloved age-old African American folktale is a return to the old woods of the soul, where something creaturely stirs and awakens something feathered and alive in us. Retold by Virginia Hamilton in her enchanting book Her Stories: African American Folktales, Fairy Tales, and True Tales, this is a story rooted in the shadowed misty forests that stretch across Louisiana, Georgia, and the Carolinas—where ancient oaks drip with Spanish moss, ferns unfurl, and wild bromeliads cling to damp branches. In the once-upon-a-now, the haunting call of the barred owl echoes through the thickets, stirring from slumber the quiet weight of choice.

This story begins with the warm, yeasty scent of bread rising and the soft hush of a cabin deep in the woods. Three women are gathered around the hearth, kneading dough, when a knock echoes through the wooden door. They pause—but do not answer.

The knock returns, louder, haunting, urgent this time. Still, they remain silent, their hands dusted in flour, their eyes avoiding one another. Outside, something unknown waits. Inside, the dough begins to swell—first slowly, then unnaturally fast—rising in its bowl, then spilling over, creeping across the table, down to the floor, growing, pressing outward as the knocking becomes pounding. By the time the women realize something is wrong, it is too late. The dough has taken on a life of its own, filling the entire room, swelling up the walls and into the rafters, pushing out air, space, breath. Desperate, they climb into the loft, and one by one, are forced out the window into the dark night.

The last thing heard is not a scream, but the beating of wings—and the low, echoing hoots of three owls circling overhead.

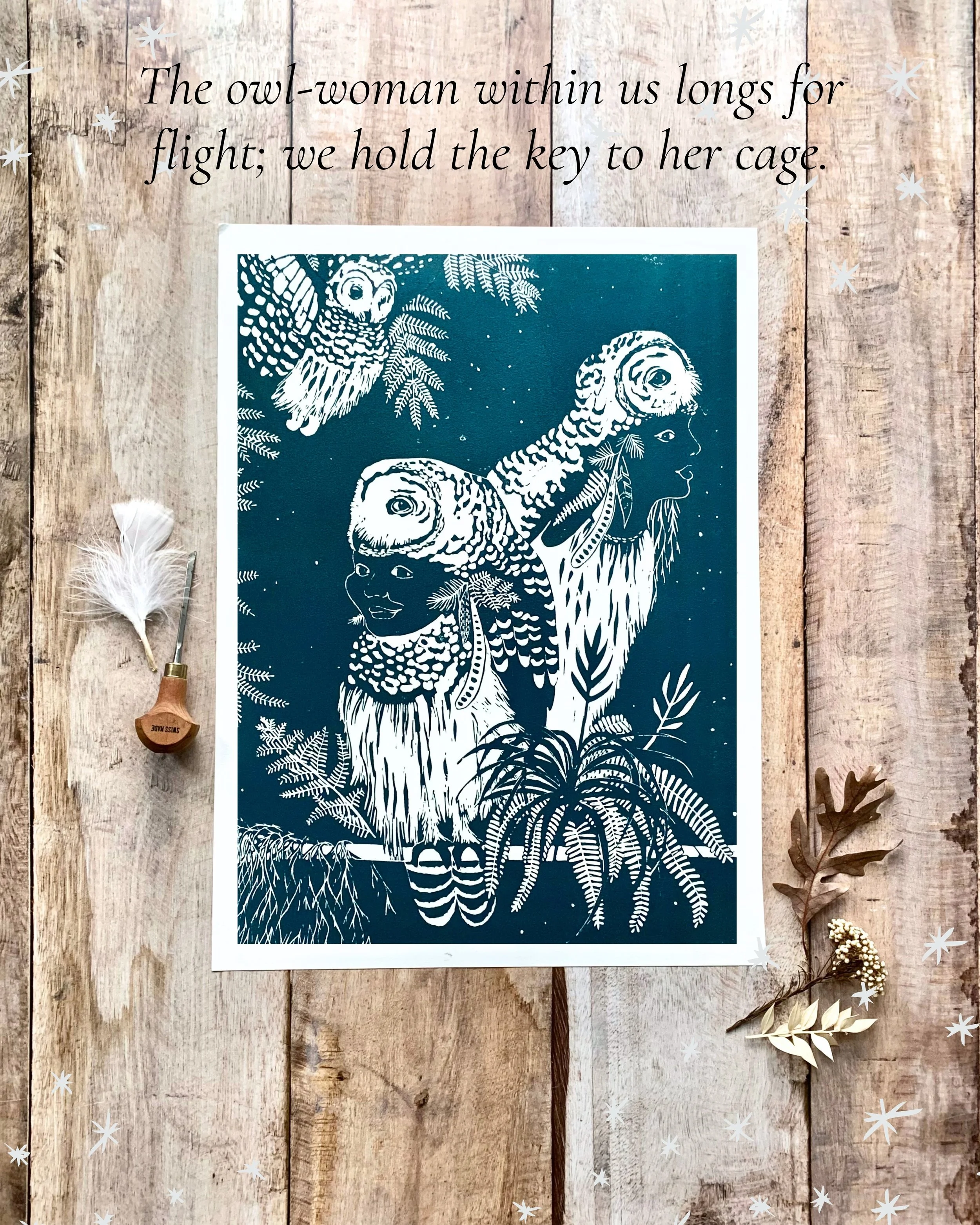

There are many interpretations for this story about three baker women who get transformed into owls. At first glance, it may appear to be a simple warning: answer the stranger’s knock or suffer the consequences. But as the dough swells and the knocking deepens, the story reveals a quieter truth—the women are caught between the comfort of the known and the call of something wilder, deeper. Perhaps the rising dough is more than bread—it is the rising of something within, something that can no longer be contained. In that moment, the tale asks: in what moments do we find ourselves at the threshold, hearing the knock of choice and possibility? Might we, too, risk unlatching the door of the self and let the bird within awaken to her flight?

Renowned Jungian Psychologist and author Dr. Clarissa Pinkola Estes in her book Women Who Run With The Wolves, puts into words to this all too familiar ache many women feel: “Inside every woman there is a wild and natural creature, a powerful force filled with good instincts, passionate creativity, and deep wild knowing”. She speaks of the Wild Self—the feathered spirit buried beneath aprons and obligations, too long silenced by polite smiles and the domestic weight of “shoulds.” Like the three women in the tale, we knead our days into careful loaves, tending to what is expected—while the knocking only grows louder. When we feed only the small safe self, we risk forgetting we have wings. The wild grows hungry in the shadow, and the daily grind—though familiar—becomes a kind of burial, layering over our radiance with each unspoken truth and unrealized calling. One day, when the knock comes at the door, something stirs and we realize only way forward is skyward. We must open the window, trust the wind—and remember we were born to fly.

According to Hamilton in another one of her books, The People Could Fly: American Black Folktales told by Virginia Hamilton, she shares her own research revealing how enslaved people used folktales about flying to imagine freedom as a possibility. She says, “There are numerous separate accounts of flying African and slaves in the black folktale literature. Such accounts are often combined with tales of slaves disappearing. A plausible explanation might be the slaves running away from slavery, slipping away while in the field or under cover of darkness. In code language murmured from one slave to another, ‘Come fly away!’ might have been the words used” Telling stories to each other about birds flying was a way to express a collective desire for freedom secretly without actually opening speaking about it.

Harriet Tubman also spoke the language of owls. Cloaked in darkness and guided by stars, she would call out with the haunting cry of the barred owl—a wild, echoing sound that told fugitives hiding in the shadows it was safe to move. The owl’s call was both camouflage and compass, allowing her to slip past danger and lead others toward the trembling light of freedom. Like the owl, she moved with instinct, with knowing, with the power of a woman who belongs to the wilderness. In the telling of this African American folktale—passed mouth to ear in hidden cabins and along secret routes—the barred owl becomes more than a bird: she becomes the voice of liberation, the keeper of the wild soul, the sign that a woman has remembered who she truly is. As Clarissa Pinkola Estés reminds us, “Go out into the woods, go out. If you don’t go out in the woods, nothing will ever happen and your life will never begin.”

Why are owls so fitting for this tale, and not other birds? Perhaps because owls are threshold keepers. They are most alert and feed at dusk and dawn. Unlike songbirds who rise with the sun, owls do not fear the shadows and the night. They move within it, eyes wide open, hearing what is hidden, guiding us through the dark woods of the soul. And so it makes sense that in this tale, it is owls who claim the three baking women, who had reached the edge of what their lives could hold. With the rising dough pressing in around them, they are forced to shed the safe and familiar. The owl is not their punishment, but their passage—an embodied mythic form for the transformation they could no longer refuse. To be claimed by the owl is to be called back to your instincts, to your wild knowing, to the wisdom that comes not from logic but from listening to what stirs beneath the surface—into the wild unknown where the self is no longer small, but sovereign.

Folktales are not merely words bound in storybooks existing outside of ourselves to read from the safety of our cozy armchairs—stories are a living leaven, inspiring something to rise quietly within us, until we’re pressed to the edge of ourselves and invited to leap. The tale of the three bakers and the barred owl calls us back to what once stirred beneath our skins: the creaturely feathered Self who is caged, and who only we can free. The choice to fly is not simply offered but demanded by something deep and old. As writer, anthropologist, and folklorist Zora Neale Hurston reminds us, “Folklore is the boiled down juice, or potlikker, of human living.” Within the wisdom of this tale, then, is a concentrated soul-food, simmered from generations of struggle, wonder, and wisdom, nourishing the parts of us that still remember how to listen, transform, and rise. Will we choose to listen?

* Many of these stories have been orally transmitted and I highly recommend Hamilton’s version of this particular one because she retains the African American Southern vernacular which gives the telling of the story so much more authenticity. Who Cooks For You! is a handmade linocut print inspired by an African American Folktale retold by Virginia

** “Who Cooks for You!” is the sound a barred owl makes.

Blog Cover Photo Credit: Aaron J. Hill on Pexels

References:

Keyes, Allison (Feb 25, 2020). “Harriet Tubman, an Unsung Naturalist, Used Owl Calls as a Signal on the Underground Railroad”. https://www.audubon.org/news/harriet-tubman-unsung-naturalist-used-owl-calls-signal-underground-railroad

Hamilton, Virginia. (1985). The People Could Fly: American Black Folktales told by Virginia Hamilton. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Hamilton, Virginia. (1995). Her Stories: African American Folktales, Fairytales, and True Tales. Beijing: Blue Sky Press.

Pinkola-Estes, Clarissa. (1992) Women Who Run With The Wolves. New York: Ballantine Books.