The earth remembers. The land, in its quiet way, carries stories older than memory—stories like seeds, waiting for the right moment to break open and grow.

“For all of us, becoming indigenous to a place means living as if your children’s future mattered, to take care of the land as if our lives, both material and spiritual, depended on it,” says Robin Wall Kimmerer in her book Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of Plants. This vision of reciprocity and reverence lies at the heart of the Haudenosaunee creation story of Sky Woman, which Kimmerer retells with grace. The story begins with Sky Woman—the first woman, “the original immigrant,” as Kimmerer calls her—and it inspired me to create this linocut print.

In the beginning, there is only water and sky. Sky Woman falls from above with fruits, branches, and seeds clutched tightly in her hands. As she tumbles toward the ocean, geese rise to meet her, softening her fall. Below, the Loons, Otters, Beavers, and Fish gather to find earth for her to land on. One by one they dive, but the water is too deep—until the humble Muskrat returns, triumphant, with a handful of mud. He places it gently on the back of Great Turtle. Sky Woman, moved by this offering, sings and dances in gratitude, scattering her seeds and carefully tending them. Slowly, Turtle’s back becomes a lush landscape—abundant, generous, and alive with the gifts she’s planted. This place, born from cooperation and care, becomes Turtle Island—the original name for North America.

I love this idea of reciprocal care that pulses at the center of the tale. Too often, we’re taught to see the wild through the lens of competition—species locked in a brutal fight for survival. But what this story, and Kimmerer’s work, reveals is a deeper truth: survival often depends on symbiosis—on interdependence, generosity, and mutual flourishing. Many Indigenous stories, including that of Sky Woman, reflect this understanding. They speak of plants and animals not as resources, but as kin.

Seeing the wild as reciprocal shifts our imagination. Nature becomes not a battleground, but a web of relationships—sensitive, aware, and collaborative. It becomes a subject rather than an object, a living force with its own voice and volition. And perhaps, once upon a time, before science drew its sharp lines, humans heard that voice more clearly. I like to believe this is how the Sky Woman story was born—from the land itself, from the listening. In this way, folktales feel alive too—woven with earth and breath and seeking us as much as we seek them. When we receive their wisdom, we are not just learning—we are being found.

Inspired by this ancient story, I created a linocut print of SkyWoman as I imagine her - surrounded by native North American wildflowers, herbs and plants: California Poppy, Cattails, Echinacea, Elderberries, Maple seeds, Mesquite, Dandelion, Prickly Pear Cactus, Valerian, and Wild Rose.

The stark black-and-white contrast of the design mirrors the duality within the story’s next chapter. Sky Woman’s daughter gives birth to twin sons—one good, one destructive—whose rivalry shapes the earth and humanity’s nature. The good twin, Teharonghyawago (“Holder of the Heavens”) or Sapling, is gentle and born in the natural way. He brings forth what nourishes life: flowing rivers, fertile trees, and food-bearing plants and animals. His brother, Tawiskaron (“Flint”) or Flinty Rock, is impatient. He forces his way out of his mother’s side, causing her death. He seeks to undo his brother’s work—creating thorns for berries, poison in plants, and peril in the animal world. Their conflict rises like a storm. When at last they meet in a final struggle, the good twin prevails, banishing Flint to the underworld—but not without cost. Their battle lives on in the world we know, where beauty walks with flaw, and the wild still hums with both light and shadow.

Though ancient, the story of Sky Woman speaks powerfully to our time. Ilarion Merculieff (Unangan from St Paul Island) echoes the values of this myth of creation in the book We are the Middle of Forever: Indigenous Voices from Turtle Island. He observes how today many are reacting to the world’s violence and toxicity, but he reminds us when we fixate on harm and darkness, we risk feeding the very forces we wish to diminish …giving energy to the very things we hope to change. Instead, he invites us—like Sky Woman—to imagine the world we long for, and to plant and tend it with intention, from the heart.

Perhaps this is the quiet offering of the story, still echoing through the land: that creation is a choice made again and again. That we are not separate from the world, but participants in its becoming. That even now, Sky Woman’s seeds are still in our hands.

References:

Kimmerer, Robin Wall (2014). Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of Plants. Minneapolis: Milkweed Editions.

Le Guin, Ursula K. (2016). Words are My Matter: Writings on Life and Books. New York: Harper Perennial.

Simard, Susan (2021). Finding the Mother Tree: Discovering the Wisdom of the Forest. New York: Knopf.

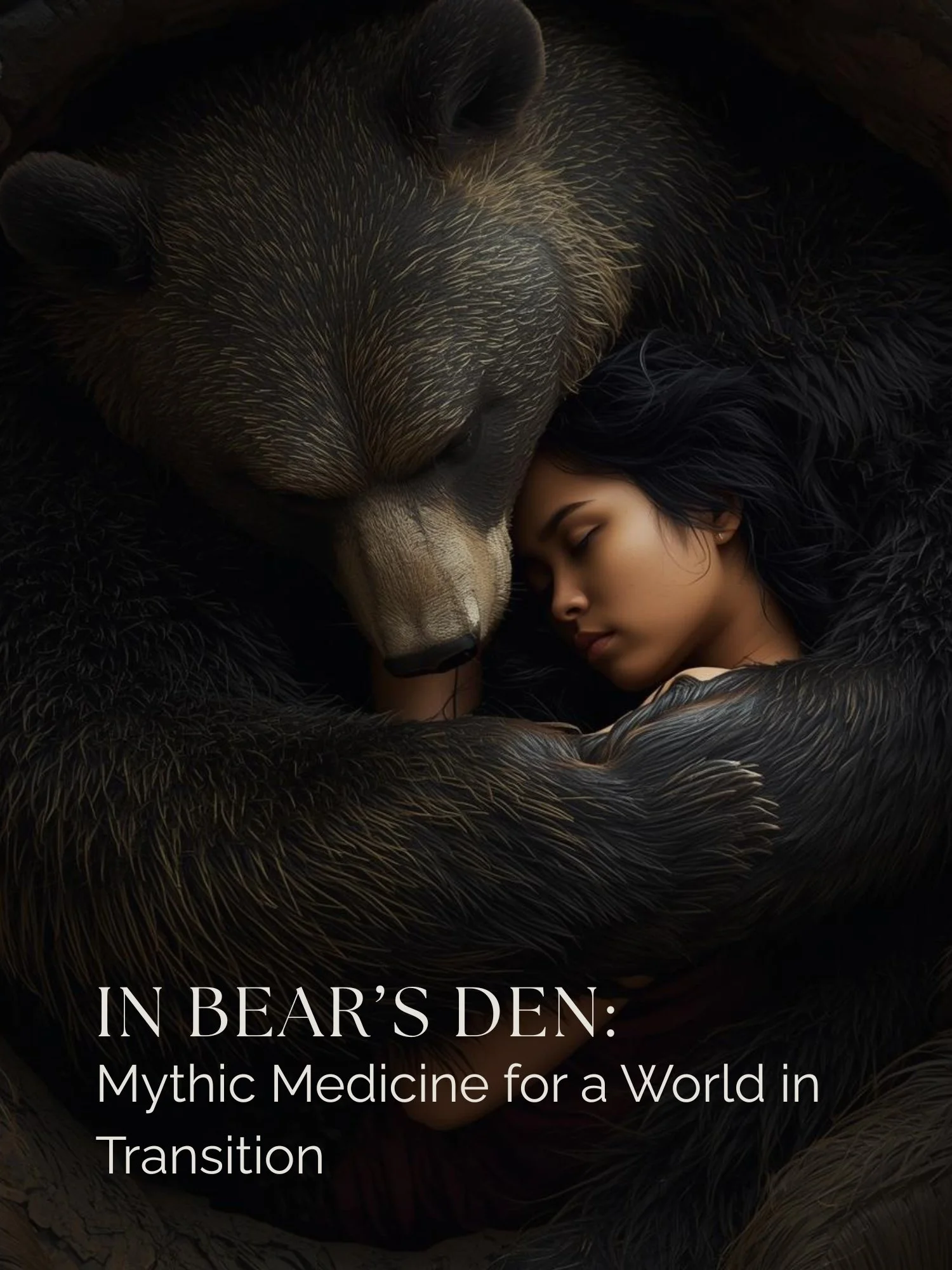

In the deep memory of our Earth, as the year turns, we witness the sun returning, brightened by the quiet tending of Earth’s creaturely beings. Across traditions, both ancient and living, these sun animals chase the sun, free it, temper its heat, and watch over it with attentive, nurturing care until dawn hatches. Within the spell of these stories, we begin to feel like we are living within a relational universe—awake, watchful, alive, and attuned. And with this sense of belonging, the stories can open a quiet space where the edges of a once indifferent world soften, and trust quietly unfurls, allowing wonder to rise as we follow the sun on its journey across the sky.