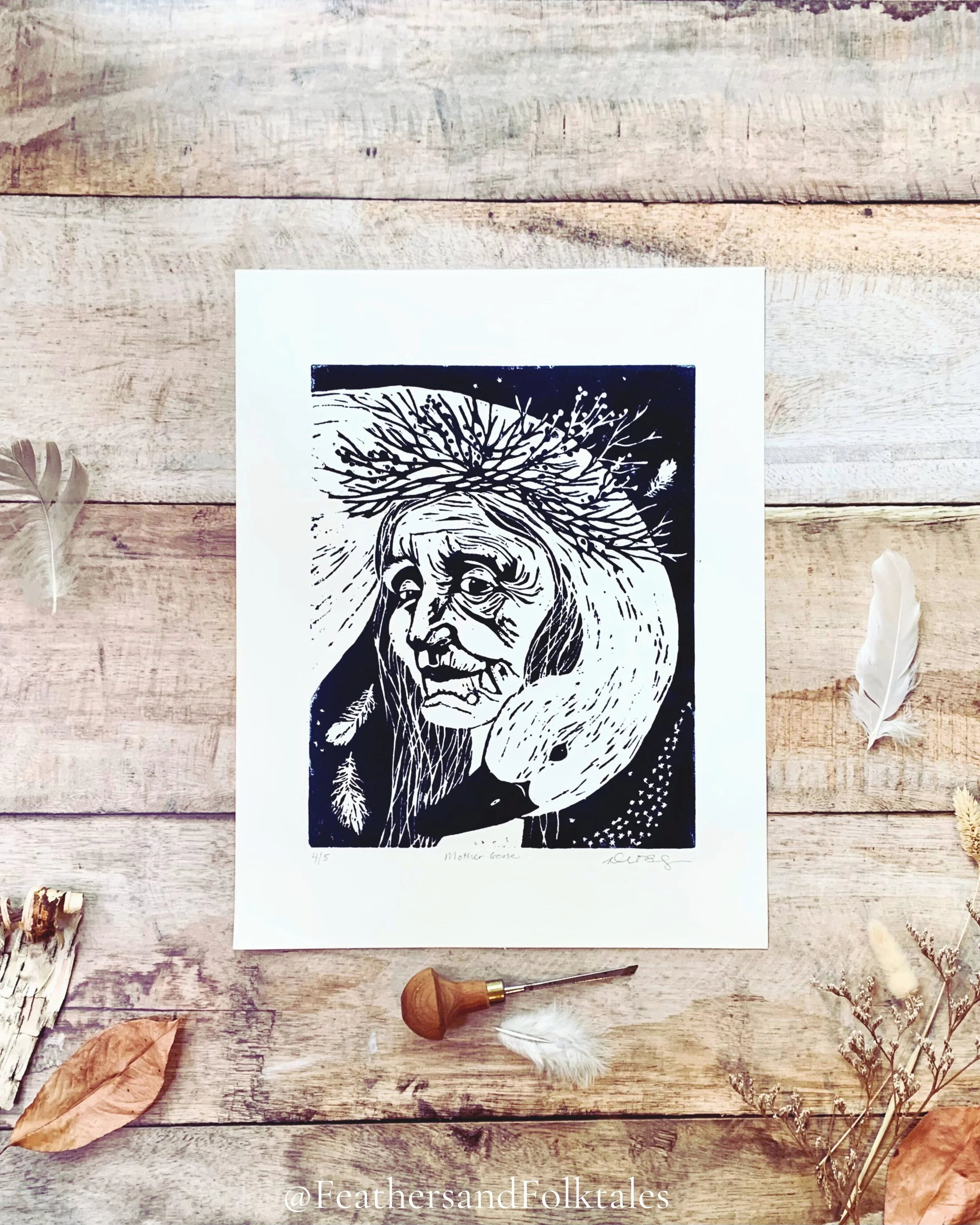

Between the covers of a Mother Goose book, children’s rhymes and folktales are woven together with feathers and threads, carrying the quiet magic of an ancient, shape-shifting spirit.

Mother Goose—also known as Frau Holle or Old Mother Frost—was collected by the Brothers Grimm in Children’s and Household Tales in 1812. Old stories whisper that she earned her name through the art of transformation, slipping between the shape of a bent old woman and a great white goose. In some tellings, she bears a single, oversized foot, perhaps shaped by pressing the treadle of her spinning wheel through long winter nights. Winter was the season of spinning and weaving, when the work of planting and harvest paused, and hands turned to quiet craft. It was also the season of stories—threads of wool and threads of wonder drawn from the same deep, creative place—binding work and imagination together, and giving rise to figures like Mother Goose, whose tales are spun from both.

Some more goose-themed winter linocuts

The Brothers Grimm believed she was a modern echo of Perchta, the Alpine mistress of winter and weaving, a pre-Christian spirit who walked the thresholds. Perchta dwelled in the in-between places—the boundary of the old year and the new, the passage from maiden to mother to crone, the frosted line where village meets wilderness, the hush between birth and death, the shimmering veil between the human world and the unseen. Her shapeshifting nature, slipping between an elderly woman and a white goose, embodies these transitions: maiden and crone, life and death, light and darkness, marking the liminal magic of the Winter Solstice. Known also as Frau Holle, she appears as both the Dark Grandmother and the White Lady, guiding infants to the spirit world while heralding the lengthening days. Her broom sweeps away the old to make way for the new, and her spinning wheel evokes the cycles of life, death, and rebirth. Through her weaving and spinning, she bridges the mortal and the magical, and in Catholic German folklore she is sometimes called a witch, said to ride on broomsticks—or even the back of a goose—carrying her power across the thresholds of worlds and seasons.

A trio of goose-related winter linocuts

Perchta is said to roam the countryside at Yuletide, the twelve sacred days between the Winter Solstice and the new solar year, a liminal time belonging neither to the old year nor the new, when ancestral spirits are thought to walk among the living. Known as the Snow Queen or White Lady, she is tied to birch trees, the first to sprout when a forest is cleared, a living symbol of renewal. As Christianity replaced Germanic paganism in the Early Middle Ages, many old customs faded or were absorbed into new traditions, yet Frau Holle survived, tucked into rural folklore and later emerging as Mother Goose.

Liminal beings unsettle hierarchies; they belong to all and none, slipping through the nets of doctrine and decree. Perchta was never forgotten—she was concealed, reclothed as Old Mother Goose, free to wander into children’s books and fireside tales, her presence preserved in laughter, rhyme, and wonder. Her power lives in the spaces between worlds, seasons, and stories, a resilient magic that endures quietly yet unmistakably. To honor Mother Goose, or Perchta, is to honor a world that never vanished, only shifted its shape—a world of transformation, of thresholds crossed, and of life that continues to shimmer in the edges of winter.

In these shadowed and fractured times, when visions of one world rise against one another, we must remember the Sacred Seamstress who eternally weaves worlds back into belonging. She appears as Na'ashjé'ii Asdzáá, Spider Grandmother of the Navajo, or as Amaterasu Omikami, the Japanese Shinto sun goddess, or the Valkyries of Norse legend just to name a few . . .This feminine archetype dwells in the shadows wearing a thousand forms and names. Perhaps she awaits within you? Now is the time to call her forth, and she will rise; nourish her, and she will flourish. Explore a few of her many faces and wisdoms in this blog.