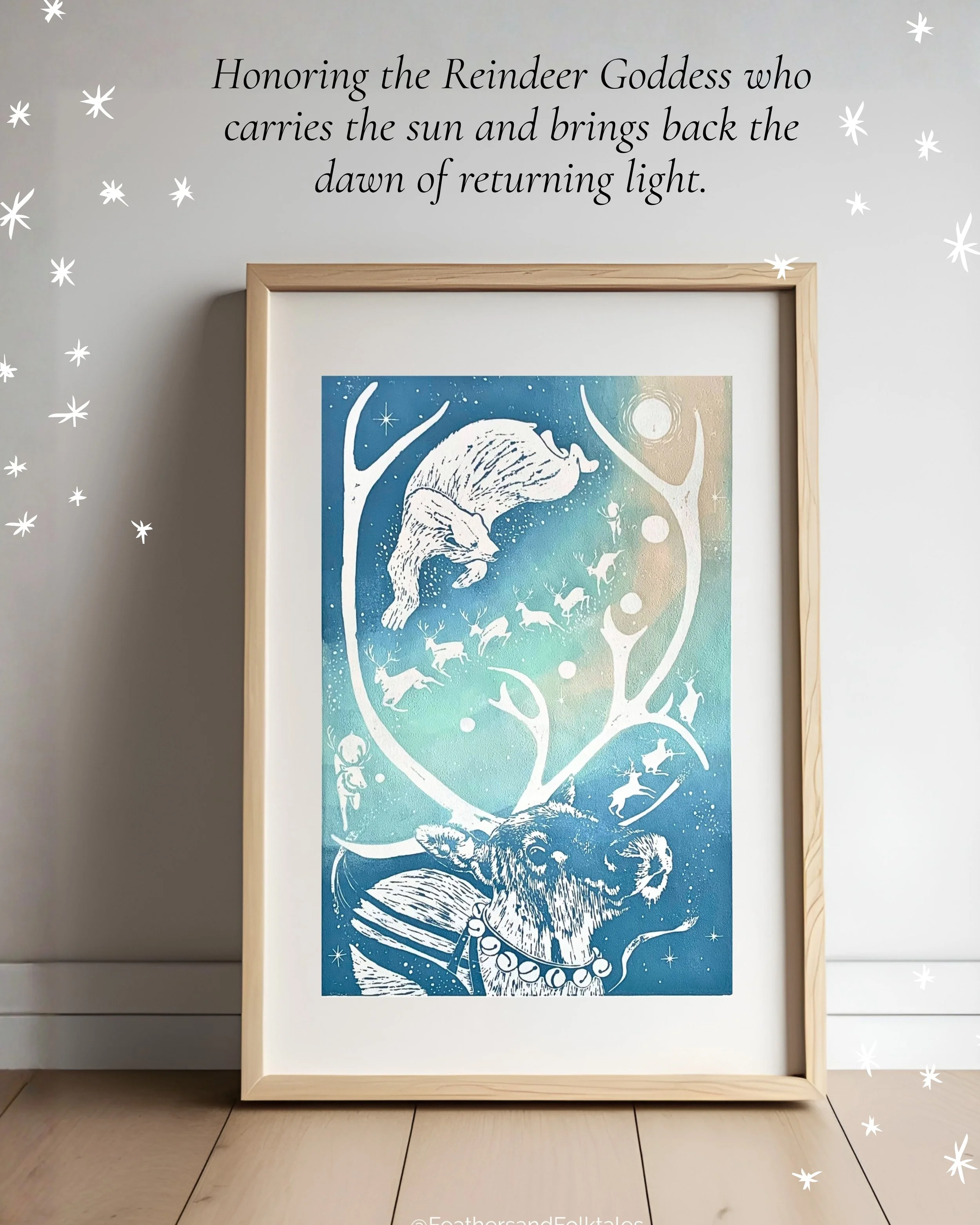

The sound of hooves, the clanking of antlers, and soft feel of fur are the beating heart of this beloved folktale about the reindeer, also known as caribou, and their connection to the seasonal cycle of the sun which draws loosely from several ancient stories from Norway, Sweden, Finland and Russia, including many elements from indigenous Sami folklore.

Some believe that long before Santa charioted his herd of reindeer across the wintery skies it was a Reindeer Goddess who carried the sun between her wide antlers bringing in the Winter Solstice. In the summer months when she shone brightly, she was pulled by a giant bear. Then as the year progressed and winter approached, her light would wane and the bear would transform into a herd of reindeer. Unlike the male reindeer who sheds his antlers in winter, it is the doe who retains her antlers during the cold winter months, so truth be told, Santa’s reindeer are actually female. . .revealing how some elements of the original folktale still live on in this beloved story many of us still tell today!

In these northern latitudes as herds of caribou are traditionally observed migrating across the landscape, they appear in human folktales like this one, serving as lyrical and poetic guiding spirits ushering in the seasonal changes. Though I am no expert in Nordic folklore, nor Sami cultures, I will just briefly share a few interesting things I learned from trusted sources that particularly drew me to this story, in order to reflect on the gift this folktale offers me.

I love how this folktale explains and normalizes the waxing and waning of the sun’s light through the seasons in the northern hemisphere. In this industrial age with the constant pressure to be productive, this story reminds us of a more ancient intelligence: of life’s ebbs and flows, and the cycle of waxing and waning which is so much more sustainable. Rather than the tick of a minute hand on a clock, or the beep of a digital device, I love how in this story the passing of time is associated with the sun’s cycles and a herd of celestial caribou.

Today so many of us live so separately from nature, rarely will we mark time according to the migration of creatures we might see outside our windows. In the modern industrial world, there is a sense that nature needs to be tamed and controlled, rather than something we look to as a guide to follow.

I find it fascinating that in Sami language “eallu” is the word that means a herd, but in contrast to English where the verb “to herd” puts humans in the position of authority, in Sami language “eallu” also means to surrender to the animals. “We follow them; they don’t follow us,” says Anders Oskal, the secretary-general of the Association of World Reindeer Herders (W.R.H.). Etymologically, “eallu” also means kin, and is also related to the word “eallin” which means life. With this in mind, perhaps we can glean a deeper meaning this folktale offers. By associating the weakening light of the sun with a herd of caribou, it may be suggesting we surrender to the the season of wintering, hibernation, reflection, and rest. . .

Pulling the print off of the block of carved linoleum. This is a photo of the first edition which includes mostly greens and blues and a little turquoise.

In the traditional Sami reindeer herder lifestyle, the caribou do offer the Sami the gift of life: the caribou offer their body as food, their hides for clothing, blankets and tents, they provide muscle power to pull sleighs, and their antlers become tools. In contrast, many of us who live in cities, are quite divorced from the animals we eat or whose hides we use for our shoes or belts. We simply refer to these animals as a generic “cow” or “pig” or “chicken” (most certainly I do!). In contrast, in Sami language there are between 400 and 500 words used to identify different caribou within the herd, enabling speakers to distinguish the caribou by color, girth, stance, stage of life, branching pattern of antlers, and even temperament. For example, the truculent female who resists the rope is called “njirru”, and the plodder whose hooves hardly leave the ground is called “slohtur”, and the one that keeps its own counsel, hovering at the fringes is called “ravdaboazu”. Perhaps it is because of this deeply intimate relationship with the caribou, that the caribou occupy a place in this folktale that is so much more than just an “it” or an “animal”. In the story, the caribou play the vital role of bringing back the sun, they play a role in the wider cosmos, and are the bringer of life every year. Some Sami believe they are descendants of the caribou and their oldest ancestor was a caribou who shapeshifts between human and caribou.

Vanessa Charkour, herbalist and environmental activist, and author of Awakening Artemis: Deepening Intimacy with the Living Earth and Reclaiming our Wild Nature (2021), writes about the power of myths and folktales in shaping our “inner ecology”, or our inner psychological relationship with the wild. Charkour says what we need at this moment in time are not more stories of climate catastrophe and doom but stories of enchantment and interconnection with the wild: stories like myths and folktales that provide us with a earth-centered lense through which we can rekindle our relationship with the more-than-human worlds. She says through story we can repair the broken relationship we have with the wild as a collective, so that we may once again be enchanted by the mystery of our Mother Earth, and be engaged more intimately with Her.

Today people may look to find magic that is manufactured by Disney or by expensive toys when really, perhaps, all we need to do is spend more time in the wild, and we will find enchantment everywhere. This is why folktales and myths are so precious, particularly at this point in history, the Anthropocene, because they preserve and carry with them so much of those lost ways of intimately relating to the landscape and wildlife. Contrary to the idea that folktales are just imaginary, or child-like, or not real, ancient folklore reveals that since the beginning of time people have been aware of how vital this sense of enchantment is for our sense of well-being, and meaning making as human beings. Folktales bring us into kinship with the wild, and help us realize to care for the earth is caring for ourselves.

Where I live in Massachusetts now, it is the heart of spring. It is that time of year when the sunset edges back later and later, enabling me to take after-dinner evening stroll while the sun is still out. In that twilight time when things take on the colors of a little dusting of magic, I can easily imagine the sun with her crown of antlers, being pulled by a herd of caribou.

Note: Though there are two different words for caribou (“caribou” are undomesticated and “reindeer” are domesticated versions of the same creature) I have used the word “caribou” consistently in this piece to refer to both.

References:

Mishan, Ligaya (Nov 9., 2020). “In the Arctic, Reindeer Are Sustenance and a Sacred Presence” (https://www/nytimes.com/2020/11/09/t-magazine/reindeer-arctic-food.html)

Shaw, Judith (December 18, 2016) “The Reindeer Goddess by Judith Shaw” (https://www.feminismandreligion.com/2016/12/18/-the-reindeer-goddess-by-judith-shaw/)

In the deep memory of our Earth, as the year turns, we witness the sun returning, brightened by the quiet tending of Earth’s creaturely beings. Across traditions, both ancient and living, these sun animals chase the sun, free it, temper its heat, and watch over it with attentive, nurturing care until dawn hatches. Within the spell of these stories, we begin to feel like we are living within a relational universe—awake, watchful, alive, and attuned. And with this sense of belonging, the stories can open a quiet space where the edges of a once indifferent world soften, and trust quietly unfurls, allowing wonder to rise as we follow the sun on its journey across the sky.